by Ande Wanderer

Go Go Magazine cover story

4980 words

“Junk is the ideal product . . . the ultimate merchandise. No sales talk necessary. The client will crawl through a sewer and beg to buy. . . . The junk merchant does not sell his product to the consumer, he sells the consumer to his product .” William Burroughs, Naked Lunch

We heard it throughout the 1990s— smack is back.

There were the movies featuring heroin use — Pulp Fiction, Killing Zoe, the Basketball Diaries, and Trainspotting.

There were the rock n’ roll causalities — Jonathan Melvoin, of Smashing Pumpkins, Bradley Nowell, singer for Sublime, New York Doll’s, Johnny Thunders, Jerry Garcia who died while detoxing from the drug, and poster boy of grunge, Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, who killed himself after a long struggle with heroin addiction.

There were controversial junkie glam advertisements, most notably, the 1996 Calvin Klein ad campaign starring a strung-out looking Kate Moss.

For every rock star or celebrity who has died or struggled with addiction, there are hundreds of MTV–corrupted youth across the country who’ve met similar fates indulging in their idols’ nemesis.

Traditionally considered to be the domain of the most down and out, the reality for the those who were sold on the ‘ultimate merchandise’ Burroughs alluded to in 1959 is that heroin has a way of seducing buyers — whoever they are — again and again.

Colorado is no exception.

According to ADAD Household Survey data, 0.6 percent of the population here has recently used heroin, compared with the national figure of 0.2.

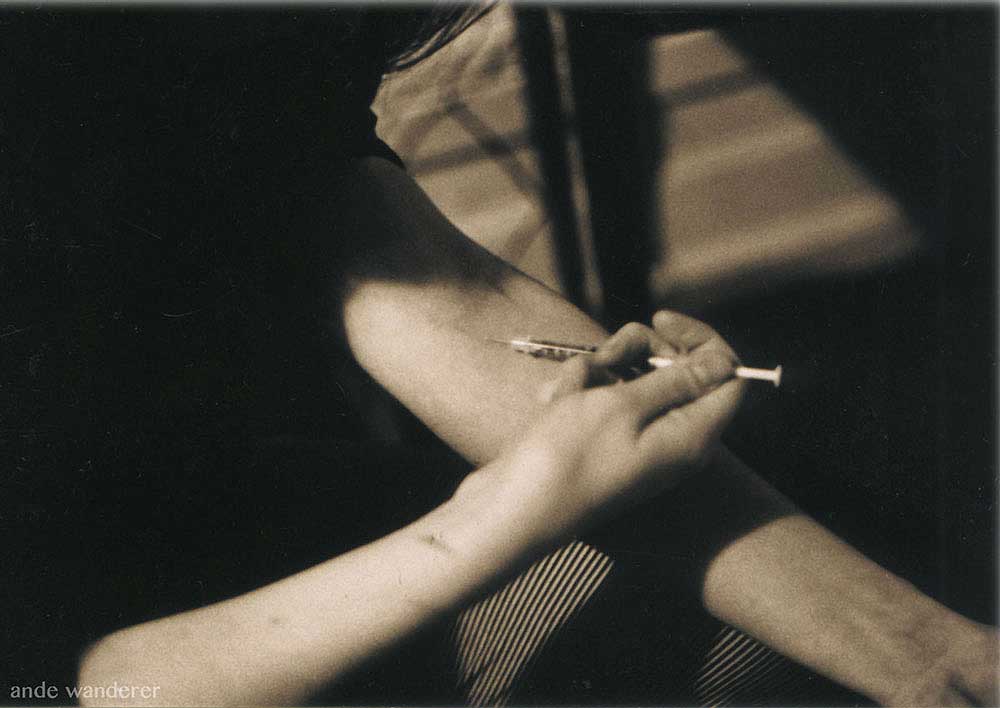

The percentage of those injecting their heroin, and for that matter, the even more pervasive methamphetamine, are higher than in other regions as well.

Health authorities are faced with a mountain of related problems in addition to addiction — the spread of injection-related diseases such as HIV, Hepatitis B, and C, tuberculosis, and overdose.

Seduction and Sickness

A few months ago, 20 year-old Darren Strazza* wandered the dim back streets of downtown Denver a desperate man. His body ached, his stomach churned, and his skin crawled.

He was dope sick, — badly in need of heroin as he had been countless times before, but something else was wrong — putting one foot in front of the other sent waves of pain screaming up his spine.

He didn’t know how he was going to manage to walk the streets to hustle himself some more chiva, as heroin is called on the streets of Denver.

He knew he couldn’t trust any junkie acquaintances to help him out. The excruciating pain overtook his dopsickness, and Strazza made himself walk to Denver General’s Emergency Room.

Within minutes of arriving at the hospital, Strazza was in the surgery ward. There was talk of amputating his legs. Turns out he had developed blood clots, which cut off circulation to his lower legs.

It was from shooting up.

“When I heard of heroin, I saw a needle in my head. I never saw myself doing it,” he says.

As it turned out, falling into a heroin habit was as easy falling for a girl. The seduction began when he was 17 and enamored with a girl who snorted heroin.

As a woman she felt vulnerable scoring for herself in the Golden Triangle area nestled around lower Park Avenue West. She taught him the magic words to cop dope on Larimer Street:

“¿A donde está la chiva?” With that little bit of Spanish, he would score Mexican black tar for his girl.

After a while of watching her consume it in front of him, and getting bored watching her be blissed out, his curiosity overtook him and he tried it.

“It was cool that you didn’t have to shoot it,” he says.

Instead they ground up the black tar with sleeping pills and snorted it.

Despite his initial aversion to injecting drugs, Strazza says he began shooting it within a month or two — it was far cheaper that way, and he liked the instant rush of euphoria that came with injecting.

Three years later, Strazza had experienced plenty of consequences of his drug use before he landed in the E.R. again — he lost jobs, got kicked out of his parents’ house, bounced from shelter to shelter, and overdosed twice.

But it wasn’t until there was discussion of amputating his leg that it really hit him that his addiction had gone too far.

He was lucky, he had made it just in time to keep his legs, but the zombie-like scars, running up either side of his shins like zippers, will remain forever, evidence of how he spent the last of his teenage years — in an agonizing dance with chiva.

Strazza is typical of a new heroin user in Colorado — they are mostly white, and mostly young.

In 1993, 9.4 percent of those entering drug treatment in Colorado for heroin addiction were under the age of 25.

In 1998 and the first half of 1999 that number jumped to 16 percent. But the trend has as much to do with economics as with Hollywood allure.

More sophisticated refining techniques in Mexico have meant cheaper, purer black tar heroin has been showing up on Denver’s streets since the late 1980s.

“Because the purity has increased they don’t necessarily have to use the intravenous method anymore. They can snort it or inhale it and still get the high, which has taken away the stigmatism that heroin is a ‘bad’ drug,” says Dennis Follett, Public Information Officer with the Drug Enforcement Administration.

According to DEA data, average purity for Mexican black tar heroin in Denver streets is 39 percent. In the 1970s heroin averaged seven percent purity.

Still, most users in Colorado, like Stanzza, end up injecting the drug after a period of use.

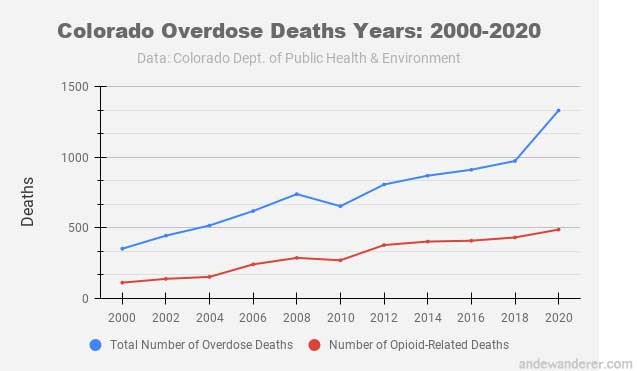

Naturally, the increased purity has led to more overdoses.

The Colorado Department of Human Services Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division reports that emergency room admissions for heroin overdose has jumped from 18.4 per 100,000 in 1993 to 32.3 per 100, 000 admissions in 1998.

In 1998, the last year for which figures are available, there were 135 opiate-related deaths in Colorado — the most ever recorded.

The overdose problem is so pervasive that health officials, traditionally concerned with stemming the spread of disease among injection drug users, have partially shifted their efforts to reducing the number of overdoses.

In mid-January academics gathered in ‘needle city’ Seattle for a conference sponsored by the University of Washington, the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, and The Lindesmith Center titled ‘Preventing Heroin Overdose; Pragmatic Approaches.’

A key points of discussion was the necessity to increase programs to distribute Naloxone (a short-acting opiate antagonist) directly to drug users, who may be reluctant to call 911 when a friend OD’s.

It happens a lot in Seattle, where the heroin comes as strong as the coffee.

Rob Clifton* says when he lived in Seattle he used the same dealer as Kurt Cobain and other rock stars whose heroin use has never been exposed.

“When you meet them and they’re sick, its not like meeting a rock star: ‘Oh wow,’ you know, it’s like, ‘Oh, they’re a sick junkie like me’ Clifton says.

Cobain was just another ‘junkie loser’ and because of his high demand for the drug, Clifton would always have to longer for his own fix, he says.

Before recently going to jail on unrelated charges, Clifton was smoking heroin about three nights a week — as long as he wasn’t shooting it, he reasoned, he wasn’t a junkie.

“I have a lot of guilt associated with shooting it,” he says, “But the only way to do it heroin responsible is not to do it at all.”

The first time he tried heroin in 1990, he didn’t like the high, he says.

“But once the puking stopped, it was like rock stardom set in. It was like, ‘Whoa, I’m in L.A., I’m on hardcore drugs – you know the story.”

Thirty year-old Daria Ricci* certainly does.

Growing up in Boulder, “It was an okay to be middle class kid and do acid all the time, or whatever,“ she says.

“To experiment with drugs was totally acceptable — it was almost encouraged among the peer group. It was like a thing to do.”

When Ricci first tried heroin in 1989, Boulder was set to become another quaint city that would experience the phenomenon of middle class, predominately white kids doing heroin.

They’re too young to remember the heroin epidemic of the late 1960s and 1970s that killed Sid Vicious, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin.

Her addict friends, “Were good kids,” says Ricci. “They came from decent homes. And they weren’t destitute, And they just ended up fucked up. I think they were some kind of fascination with the dark side of it all.”

Some of her friends outgrew the urge and went onto other things, Ricci says, but she made it her lifestyle.

After a couple of years of chasing the ultimate high with trips across country and to Mexico to score drugs, Ricci was a certifiable junkie.

The once fun, bright-eyed, happy girl eventually landed in Denver and got a job at the Red Garter, an all nude dance club, that before it closed down had the reputation of one of the sleaziest in Denver.

She still remembers the terror she felt the first time she took the stage in front of skittish businessmen and unemployed regulars in her standard issue white panties.

She took on a stage name and got stuck into a dismal daily routine: wake at dusk, go dance naked in front of creepy men, head straight to Larimer Square after work to score dope, go home, get high, and sleep all day before repeating the cycle all over again.

“It was like I got buried for a few years,” she says.

When the heroin wasn’t doing the trick anymore, she added cocaine to the mix to make speed balls.

It was several stripping gigs later, when she was working at the Bustop in Boulder that she hit the proverbial rock bottom.

Though being in Boulder meant that among her customers were old acquaintances, schoolmates and even friends of her dad she’d have rather not seen under the circumstances, she made more money there, allowing her habit to grow.

When she got thrown in jail for carrying paraphernalia lost her lucrative job there, Ricci, who had also been supporting her boyfriend’s habit, turned to crime.

The duo did home burglaries, stealing anything of value, along with checks, credit cards and I.D.’s

With the checks they were able to get cash at drive-through banks, and with so many aliases and a steady rotation of cheap hotels, they avoided getting caught — for a while.

Desperation for a fix eventually led to recklessness though.

The modern day Bonnie and Clyde stole cars, a cop’s glock, and at the risk of revenge, dope from the dealer.

Soon her nightly ritual was to sit down in front of the t.v. for a fix and listen for news reports of her crimes — the pair even had a nickname in the press: ‘the CD Bandits.’

After her boyfriend got thrown in jail, Ricci was faced with feeding the need of her addiction and the fear of being wanted by the police while on her own.

“I weighed 85 pounds. I was disgusting,” she says, “I knew I had to quit.”

She relocated to her mom’s house in New Jersey. She hoped the change of scenery, and having a stable place to live would enable her to quit.

It worked for a couple of months, but she started using again and went back to crime to feed her addiction.

A cop happened to be around the corner when she tried to rob a gas station with a new boyfriend. She was busted.

She was sent to an all-female Catholic rehab program in upstate New York, but the ‘deprogramming’ tactic of the facility didn’t work for her — she escaped and met up with her boyfriend while he was out on bail.

The fugitives traveled around the U.S. for a couple of months to avoid getting caught. But the constant fear of being wanted became overwhelming and they decided to turn themselves in.

Ricci was sentenced to six months in jail and served four before then being sent to a long-term non-religious treatment program that allowed her to finally kick the habit for good.

Today she lives in a quiet neighborhood of Queens, New York, works an office job, is in a long-term relationship and doesn’t do more than smoke a little pot once in a while.

“Now I just appreciate life, getting up, not being sick…I’d rather go ride my bike or something, you know? … It’s unfortunate that I spent my 20’s doing that.”

Ricci shrugs off her positive Hepatitis C status, the most lasting physical consequence of her years of drug use, the severity of which catches up with some users later in life.

Hepidemic

Four million Americans, 72, 000 in Colorado are infected with the blood-borne disease known as Hepatitis C Virus (HCV).

Up until 1989, the disease was referred to as non-A, non-B hepatitis, but it is a more serious disease than the other two strains, for which there are inoculations.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that 50 to 80 percent of injection drug users (IDU’s) are infected with Hepatitis C within 6 to 12 months of beginning intravenous drug use.

Sharing needles is the most common transmission method for HCV, but it can also be spread through sexual contact, unsanitary tattoo and piercing practices and sharing straws to snort drugs.

Because it can only be detected with a blood test, those who are infected can go for twenty years or more without experiencing symptoms, or only experiencing mild symptoms such as fatigue and poor appetite.

Less than half of those who carry Hepatitis C in Colorado know they have it. A lucky few may never know; they will naturally purge the illness from their body. Others will develop scaring of the liver that can result in deadly cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Fifty one year-old Carol Jones* says her husband, Mike was her best friend.

Though he died nearly two years ago, she still speaks of him in the present tense. They shared a destructive love of heroin and the desire to settle down and have a family, to try and attain some sense of normalcy, despite the drug.

They found out he had Hepatitis C (HCV), or Serum Virus, as it was called then, about 15 years ago. The disease deteriorated his liver and complications required that he have his hips removed, after which he was ordered to use a wheelchair.

The 325 pound biker, once part of the tough 91/2er’s gang, basically ‘rotted away’ after that, Jones says. It was a long, slow, painful death.

Carol, who stopped using heroin years ago, carries the virus as well. She is able to work in construction, but she tires easily.

Carol’s daughters, in fear losing another parent, have her on liver promoting herbal remedies – there’s no cure for HCV but eating healthy and avoiding alcohol can slow the progression of the disease.

A hepatitis C study conducted last year by Boulder’s health department concluded that of 75 participants in their syringe exchange program, 80 – 85% were positive for HCV.

The results, says Works Program Director, Terry House are, “scary and sad” — all they can do is try to catch younger users before they become infected.

The results also mean that despite Boulder’s proactive approach in addressing HIV prevention, they can’t become complacent about it either.

Hepatitis C is four times more common than HIV, but awareness about it is limited. Calls put in to several health clinics around town about hep C testing got us responses like “Hepatitis C? What’s that?” and transferred to inoculations. Colorado receives no federal money for prevention or screening of Hep C.

Last year, the state took matter into their own hands and dedicated $200,000 toward an education, prevention and screening campaign taking place this year.

Testing is available through the public health department and the Hep C Connection, a Denver-based organization for Hep C patients.

A Health Emergency

To many, the idea of permitting distribution of paraphernalia for illegal drug is uncomfortable, at best.

Opponents say it doesn’t address the underlying issue of drug dependency, but there’s no question that needle exchange programs are an effective way to stem the tide of HIV and HCV cases.

In Liverpool, where needle exchange has been in place for a long time, there is a 0.01% rate of HIV transmission. Proponents site economic benefits to syringe exchange — its a lot less expensive to hand out needles they say, than to treat AIDS patients on taxpayer roles.

Today there are approximately 100 needle exchange programs across the country.

With Denver’s higher than normal percentage of IDU’s among it’s heroin users, and Boulder’s Works program up the road, Denver’s absence of one is rather conspicuous.

Denver agencies like Urban Peak and Project Safe, a University of Colorado research project, do have the power to distribute ‘bleach kits’ through street outreach.

Rising used syringes out with bleach does prevent the spread of HIV and HCV, but among the drawbacks from a public health perspective, are that it doesn’t address safe disposal of used syringes, therefore exposing users’ families, sanitation workers and the general public to disease. Repeated use of needles also ensures more IDU’s end up in the E.R.. with abscesses and other complications.

The Colorado House of Representatives killed a bill before them in 1997 and 1998 that would have permitted needle exchange programs.

The bill had the support of the Colorado Department of Public Health, the House Judiciary Committee, and Mayor Wellington Webb.

Webb, who was initially resistant to government-sponsored needle exchange programs, also proposed an ordinance in 1997 to allow three needle exchanges to open in Denver, but a state paraphernalia law prohibiting needle distribution blocked implementation of the program.

Denver Police appeared to be the only vocal opponents of the idea. Denver PD spokesperson, Virginia Lopez, says, “We look at it as the possible promotion of drug use, versus looking at it from the angle that it could prevent negative things that could occur from sharing needles. We just thought; Why promote it? Why make needles more accessible?”

Still, Lopez and an officer we talked to in district six had the misconception that Denver did have a needle exchange program in place. There is an illegal underground needle exchange, an unofficial extension of Boulder’s Works program, but current law calls for arrest and a $100 fine for carrying needles in Denver.

Boulder’s Health Department simply declared a ‘health emergency’ to skirt the same law that prevented Denver from implementing a needle exchange program.

In 1988, they started The Works, a syringe exchange program that was one of the first of its kind in the country, further noteworthy for its existence in a small college town.

“Being Boulder, and being more progressive, the element was certainly right,” says Program Director, Terry House.

“I’ll tell you right up front, treatment is not a focus of the program,” she warns. “What we try to do is educate.”

Once IDU’s are drawn in, they can be offered information on HIV and HCV and be led to treatment and other appropriate programs.

The Works has three part-time ‘needle delivery’ outreach workers, and a pool of around 50 trained volunteers. The volunteers, who are usually themselves IDU’s or ex-IDU’s, get a red hazardous waste container to dispose of used syringes, condoms and educational materials to distribute.

“Heroin is easy to glamorize, “ says 50 year-old Works volunteer, Al Ferguson*.

“I couldn’t say enough good about it, but, i can’t convey the horrors of it.”

With his long hair and prison tattoos, he says, the young folks he distributes needles to think,“This is a cool dude, he’s been there and back.”

Though the factory supervisor hasn’t done heroin in four years himself, he doesn’t proselytize about the dangers of drugs — they’ll do it anyway, he says.

In 1971, before the new generation of heroin users he helps were even born, Ferguson was almost finished with his degree in mathematics from NYU. He was being courted by corporations such as Dow Chemical and McDonnell Douglas.

Vietnam was dragging on, and in keeping with the times, Ferguson didn’t feel right about taking a job computing missile trajectories, so with a semester of school left, he bailed out.

He hitchhiked to Colorado and hunkered down with his confusion and his drugs to begin a thirty-year torrid relationship with heroin.

Since then, he’s spent eleven years total in prison, including time served in Mexico, luckily cut short with a bribe.

During all the years he served he was able to maintain his drug habit — getting needles was the difficulty. Ferguson remembers reusing the same rig for a year and a half, other times he would share works with eleven other guys.

Though he was treated with methadone maintenance for a total of 16 years, he continued to use heroin throughout. The last time he was thrown in Denver County Jail, he was unable to cop dope and was forced to detox from both drugs simultaneously.

He was a quivering mess, unable to eat or sleep for a couple of weeks. He was only given blood pressure medication to ensure he didn’t die.

The withdrawal, particularly from methadone, was so painful, Ferguson had a moment of clarity and decided to quit both habits then and there.

“So many of my friends are dead or in prison. I thought, well, maybe I want to live to be a little older.”

He wants to see those he helps live longer too. “I’m not trying to change their life or nothing, I’m just glad they’re being safe.”

Methadone – Maintenance or Madness?

“You want to know the trick to score drugs in any city? Just go to the methadone clinic.” says Clifton, the ex-heroin user behind bars.

Indeed, the now closed fast food restaurant across from Denver General’s methadone clinic was nicknamed ‘McBenzo’s,’ because of the abundance of drugs that could be bartered or bought there.

On June 15, the Associated Press reports, the DEA broke up an Mexican-based multi-million dollar heroin ring that smuggled 80 percent pure heroin into the county using kids and the elderly as mules.

According to the DEA, the gang used employees to target users at methadone clinics in Denver and other cities.

Despite the inherent opportunity for reduction of risk for disease and death that methadone provides, most users continue using other narcotics while on it. Others hawk their take home supply, and get heroin instead.

Ex-user, Ricci found methadone to be a convenient supplement to her smack habit. It once enabled her to take an overseas vacation with her family without suffering withdrawals. Other times she would water down her take-home supply and sell it to get the real thing.

“The goal of methadone treatment is for the person to maintain abstinence and to develop appropriate skills and change their behavior,” says Dr. Lisa Darton, Medical Director of Denver General’s Outpatient Methadone Treatment Program.

“A lot of people were into criminal behavior, not working type of thing and the whole goal of treatment is to try and make the person function better in society. So for a lot of people, after the first year, they develop enough coping skills that they can detox off methadone — some people it takes a lot longer, its more of a lifelong process and they never detox.” Darton admits,

“There is a 70 percent relapse rate for methadone withdrawal within the first year — it’s really hard.”

But she maintains, “The premise is that it is preferable to get someone on methadone than risk them contracting HIV or Hepatitis C.”

Even those who are completely opposed to methadone maintenance can find merits in special circumstances — for pregnant women, methadone protects the fetus from repeated withdrawal.

And in cases of HIV positive users, the consistency of the dosage can strengthen immune systems, weakened by varying purities of smack.

Carol Jones has been on methadone the last 20 years and has been able to lead a relatively normal life. But even though she’s apparently a methadone success story she’s been struggling to decrease her meth dose over the last several years and is among its many harsh critics.

“It’s not worth what it does to your body. Oh shit. It rots your teeth, weakens your bones, you can’t walk as well.”

She is also tired of jumping through the bureaucratic hoops to get her medicine.

Recently, a new counselor at the clinic has started reinforcing requirements to attend counselor-led group meetings, something she hadn’t been doing for years.

“I don’t want to go in there and listen to old war stories, you know?”

Those who have used methadone longterm can’t help but allude to some inherent evil quality in it.

“I’d rather see the kids stay on heroin (than start methadone),” says Ferguson. His reasoning is vague; “It just kind of gets in your bones.”

Clifton describes taking methadone as an ‘itch you could never scratch.’

Kicking it is, “like nothing I can explain.” says Jones. “It’s harder than kicking regular heroin, ‘cause I’ve done both and I tell you what — there ain’t no comparison.”

“There’s no official health department stance on it, but personally I don’t have a problem with it.” says House, the Director of The Works.

“I’ve known clients that I’ve seen one time that were using really heavy, and you see them a month later, and they say, ‘Hey, I went on methadone,’ and they look like different people.”

Some people do say it’s trading one (drug) for another, but I’ve seen people who’ve been on it for fifteen, twenty years, who are able to go about their daily lives, and its made all the difference in the world. They’re going to work, they’re having relationships. They’re living their life like anyone else.”

What even well-intention public health officials can’t know though is the stigma of being a methadone recipient.

Jones, says she’s always worked two jobs to pay for her medicine instead of getting on the dole, but still, “They just assume that the minute that you’re on methadone that your the ultimate junkie — drudges of society, not that you’ve always maintained your home, taken care of your children, had jobs… That’s what I’m going through right now. It just makes me madder than hell. “

“I see these young kids in there, putting ‘em on methadone that the court ordered and it’s stupid.

“The other day when I was in there (Denver General’s Outpatient Clinic) to pick up my three bottles at nine or ten o’clock, these three boys walk in and they didn’t look a day over 16,” she says.

“They may be hooked on some stupid little muscle relaxer or something…Putting them on Meth, it’s the worst damn thing they can do.”

“But, it’s a money thing — it’s a money maker,” she says.

Indeed, the cost of the program including methadone and therapies averages $140 per month.

Darton says the pink elixir certainly isn’t given out as freely as Jones seems to think.

“There are pretty strict state and federal guidelines. The person has to be chemically dependent on opiates for at least six months or more.”

A potential methadone participant must pass a ‘confirmation of addiction’ which includes monitoring vital signs to confirm withdrawal. For a user with less than six months of use under their belt, “The guidelines are a little more lax,” however.

In that case, they are put on methadone with detox being the goal of treatment.

Even Darton agrees, methadone isn’t always ideal. The problem is, there’s not many alternatives to methadone available to address the physical withdrawal symptoms of narcotic use.

One alternative emerging is ‘Rapid detox,’ a quick fix solution where addicts are put under anesthesia while undergoing withdrawal. Not much research has been done on this method, but critics say it’s a Hollywood remedy, expensive and not effective for long-term abstinence. A new drug called buprenorphine shows promise, but has not yet been approved by the F.D.A.

“I would say that they should not allow anyone to be on methadone or methadose (generic methadone) for more than a year — that it should be a withdrawal thing.” concludes Jones.

“But they should have counseling or some type of programs to help them get the inner strength they need to stop. To make them like themselves, but I mean that’s a tough job right now, cause we got a lot of shit coming down that kids just don’t want nothing to do with, and I can’t blame them.”

Clifton says he’s not receiving methadone and off opiates while serving his jail sentence, despite how easy former prisoners like Ferguson say it is to cop drugs in there.

“When I went to Denver…I did put to rest a lot of ghosts including d-o-p-e.” he writes from jail, “I’ll never do that again. It’s too devastating…I’ll stick to beer.”

Darren Strazza, who detoxed while he was in the hospital, now has six months clean.

He had heard the stories and purposely avoided methadone, but he is participating in outpatient drug treatment, making his chances of long-term recovery more likely than Ferguson’s according to addiction experts.

“Once you’re off it, it’s mind over matter, If I relapse even once, I’ll have to start all over,” he says.

Since he’s been clean, he’s earned his G.E.D., started a new job and will be getting an apartment this week.

His torrid affair with heroin is over, he insists.

“It’s cool not to even think about dope — I’ve gone to far to jack it all up.”

Perhaps, once again, he’ll be one of the lucky ones.

END

* Names have been changed to protect the guilty

When I first moved back to Denver from NYC, I was offered a job at the University of Colorado’s Harm Reduction program, as initially in my college career Harm Reduction was my focus.

I didn’t think that particular job offered enough money to justify waking up before dawn, so I just continued freelance writing. But I wanted to bring attention to the devastation of the opioid epidemic, which has only gotten ten times worse since fenty hit the scene.

This story was originally pitched to the Boulder Weekly. They passed, but I did get a call from my editor there who congratulated me for managing to pull all the threads together.

Now I am eager to write about how Harm Reduction is a decades old public health measure that is now obviously not working as intended.

Back then, even conservatives could get on board with Harm Reduction because it was economically advantageous. But the aim was to reduce HIV and Hep C transmission — not use all of a municipality’s health resources administering Narcan to ‘frequent flyers,’ as those who OD frequently are called.

From May 2019- May 2020 there were 81,000 deaths from O.D. in the U.S. The highest number ever in a 12-month period.