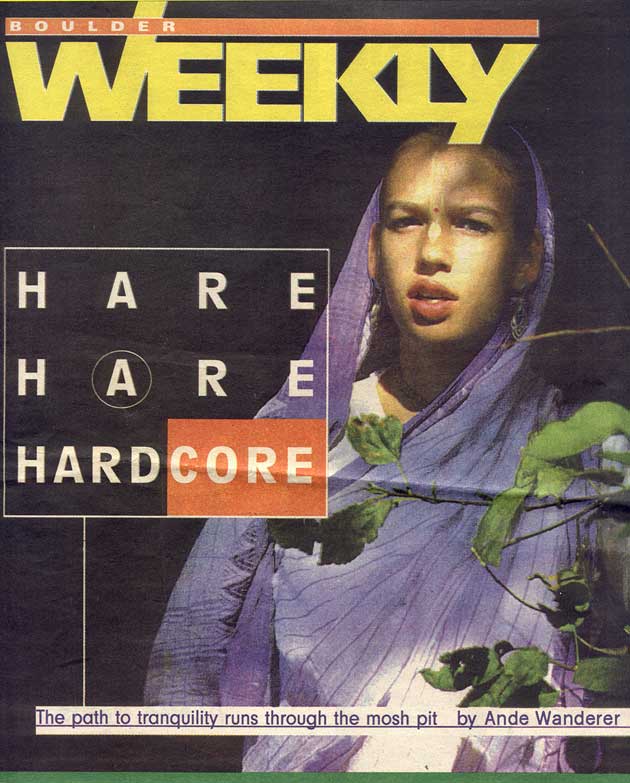

Hare Krishnas drew new devotees in the ’90s thanks to the mosh-pit friendly melodies of ‘krishna-core,’ a spiritual extension of the ‘straight-edge’ punk scene.

You’ve seen them giving away food at the Pearl Street Mall or at the airport hawking books, maybe you’ve heard them on the radio. Yep, it’s the Hare Krishna’s — hard to miss with their ‘Krishna haircuts’, saffron robes, and incessant chanting.

Boulder’s only Hare Krishna temple recently shut down due to lack of funds, but they promise to be back.

The movement has new life thanks to ‘krishna-core’ a spiritual extension of the ‘straight-edge’ hard-core music scene which advocates living a ‘straight’ life by abstaining from drugs and alcohol, and for most, illicit sex and meat-eating.

The most well-known krishna-core bands, Shelter, 108, and the Cro-Mags have appeared on MTV.

Wax Trax Records dubs the Cro-mags “one of the best hard-core bands of all times.”

Chip Brokaw, an employee at the Denver store, says they sell at least one CD a day featuring those bands. Typically the Krishna-core customers are male, ‘straight-edge’ and between the ages of 15-19.

Twenty-four year old Littleton native, Madan Gopal (who legally changed his name from Mike Day) started going to the Denver Krishna temple at the age of fifteen.

Before joining the Krishnas, Gopal and ‘Godbrother,’ devotee Pat Swanson, a long-time friend, had several straight-edge bands between them: Fury, Distance, Velcro Overdose and Full Count, to name a few. Their last band before becoming full-fledged temple members, Maintain, incorporated Krishna Conscious lyrics.

“Straight-edge is like Krishna-Consciousness with out Krishna.” says Gopal.

“It’s about being a vegetarian and doing something positive in the world. But everybody screamed about the problems and not solutions. Things I was doing before felt like a dead-end. There’s a whole spiritual aspect to life that I had never experienced before.”

For Gopal it all started at a concert in 1988 when he met Ray Cappo, aka Ranghunatha Dasa, from Shelter, who turned him onto Krishna Consciousness.

Cappo also had a spin-off Krishna influenced band, Better than a Thousand, and put out a spoken word CD about Krishna Consciousness.

“Shelter have inspired so many people to get into Krishna,” says Jason Heller from Wax Trax Records, “even though in general that type of music isn’t really conducive to worshipping Krishna, I would think.”

Heller compares the Krishna-core concept to Christian ‘death-metal’ bands.

“Christian metal sounds really evil,” he says, “but they (Christian leaders) probably realize that it recruits a lot of people, so they tolerate it.”

One of Swanson’s bands, Keep in Mind, put out a single and opened up for Fugazi at Denver’s Aztlan theater in the late eighties.

Now, he and Gopal only play devotional music at the temple worshipping Krishna.

“One of the reasons I was so attracted to hard-core is because I was just an angry person,” explains Swanson.

“It was a release to get on stage and scream about what makes you angry, but after some point you say, well what makes you angry? How can you change it? What’s the solution? And then by practicing Krishna consciousness, or any religion, the spiritual practices make you become more happy and peaceful. So I kind of lost my taste for that angry music.”

He adds that the hours are too late for full-time ISKCON members who are required to appear at morning services, long before the crack of dawn.

“But you know if I thought it would be successful (in recruiting new devotees) I could see myself doing it for Krishna. It’s a powerful way to reach people.”

From hippies to hard-core

What some describe as Hindu Fundamentalism, Krishna Consciousness is a monotheistic religion worshipping Krishna, the blue, flute-playing love stud of Hindu scripture.

Properly referred to as ISKCON (International Society of Krishna Consciousness), the movement was brought to this country from India by A.C. Bhaktivendanta Swami Prabhupada in 1966.

He started with a modest storefront in New York City’s Bowery district, drawing hippies with prasadam, or karma-free food, festive chanting, and promises to ‘stay high forever.’

Today ISKCON claims over one million followers in 325 temples worldwide.

Prahupada’s first disciples discovered music as an avenue to attract new devotees.

In 1967 a devotee organized the ‘Mantra Rock Dance’ at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom.

Beatnik Allen Ginsberg introduced Prabhupada, who led in chanting before bands like The Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape played to a receptive audience for the minimum union wage.

Throughout the concert, images of Krishna flickered on the wall as a crowd consisting of Timothy Leary, Augustus Owsley Stanley and other icons of the era watched. Against the tenants of Krishna Consciousness, someone even spiked the punch with LSD. The Hell’s Angels handled security.

Five months later on the East Coast, the Krishnas held the ‘Cosmic Love-In’ in New York’s East Village Theater.

The maha mantra (Hare Krishna Hare Krishna, Krishna, Krishna, Hare, Hare, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama,Rama, Hare, Hare) showed up on the soundtrack to Hair.

George Harrison, with the help of Paul and Linda McCartney, produced a recording of the mantra on Apple records. The ditty hit the British Top Ten. The ‘supreme’ Prabhupada even stayed at John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s English estate in 1969. Soon after, Harrison donated the Bhaktivedanta Manor estate, outside of London, to the movement.

Cozying up to Krishna

“If you see, externally some of the far-out things about our religion, like the fact that we believe God is a little blue cowherd boy who hangs out with milkmaids, you would think, you know, these guys are really sentimental and they don’t have any philosophy,” says Gopal, “but we have whole substantial, deep philosophy behind that too.”

Arguing that most religions don’t have a physical conception of God, he adds, “Why couldn’t he be a little blue cowherd boy?”

The few things that American’s might claim as their cultural fiber — popular entertainment, professional sports, and commercialism, ISKCON rejects as “maya,” or things of the material world.

Devotees can’t indulge in any vice, including coffee, tea and cigarettes. They can’t eat onions, garlic or any type of flesh. They can’t own personal items beyond clothes and a toothbrush.

They must spend several hours a day chanting the maha mantra, a minimum of 1,788 times (16 rounds, 108 times each round).

By tapping into the straight-edge movement in the last decade, the Krishnas, have gone to the other end of the cultural spectrum from the original hedonistic hippies converts — many who had extensive drug histories, mental illness, or long rap sheets before joining.

Straight-edge kids already have shunned indulgence, so they are ideal candidates to recruit for the strict Krishna lifestyle, as simple and disciplined as it is.

They believe that by living a life only dedicated to serving Krishna through bhakti-yoga, or devotional service, one can break the cycle of reincarnation. Everything they do must be for the sole purpose of serving Krishna.

Krishna’s consider themselves Brahmins, the highest ranking in the Hindu caste system, because of their austere lifestyle.

“They sincerely follow the customs of Hinduism,” says software engineer, Krishnan Kannan, a native of India’s state of Tamil Nadu, who has been attending Denver’s temple with his wife and mother for five years.

“They give a lot of food to people. I really like that.”

Denver currently has no Hindu temple, so about thirty-five percent of the attendees at the free Sunday feasts are East Indians who were raised Hindu.

“In India you can’t really dance in a temple,” says Kannan. “Here it’s different — you can dance.”

In ‘old school’ Krishna Consciousness there are essentially three types of people: ‘devotees’ who have dedicated their lives to serving Krishna; ‘fringies’ who often live near temples and believe in the religion but have trouble adhering to the rules; and ‘Karmis,’ most folks, who are viewed as lost souls building up a karmic debt as the sum of their actions.

ISKCON devotees are taught to only associate with ‘karmis’ with the aim of teaching them about Krishna Consciousness — proselytizing is viewed as major way to get in good with Krishna.

“I go out to the airport, and I talk to, the so-called Karmis all day long. I’m not bothered by their association,” says Gopal, “but I’m not, like, wanting to get out there and meet some straight-edge kid and hang out with them. It doesn’t really interest me anymore because I’m satisfied doing this.”

“We try to avoid material association with people,” adds Swanson. “So if I’m talking with some one I try really hard to, in a non-fanatical way, talk to them about Krishna.”

Sex is also forbidden, except between married couples, and even then, devotees can only get their groove on once a month — and only for the purpose of procreation. The idea is to go through life with as little sex, and thoughts of sex, as possible, for spiritual purity.

“It is difficult for me,” admits Swanson, “but when you practice a spiritual life. You taste higher pleasure, so it helps you give up your lower bodily pleasures.

Newlywed Gopal adds, “It’s more difficult to get married. When you’re not married it’s not there — there’s no possibility, so it’s not on your mind.”

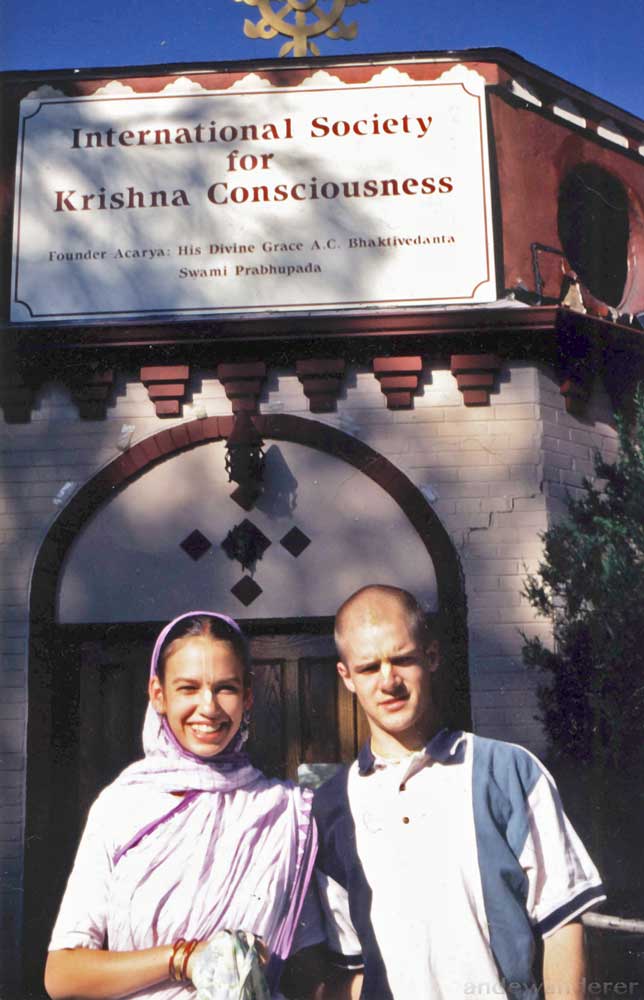

Gopal was a Sannyassis, or Krishna monk, for several years until the couple that ran the Denver temple arranged a marriage between him and their eighteen year-old daughter, Pancha-Tatva. Pancha didn’t dispute the arrangement. She says she knew Gopal, liked him, and being raised in Vedic culture, had been prepared to accept such an arrangement as natural.

Until a few weeks ago, the couple ran the now defunct Boulder temple, where they supported themselves by making samosas, Indian stuffed-pastries, to sell to health-food stores like Wild Oats.

With Boulder’s high cost of living they had trouble making ends meet, so they temporarily moved back to Denver.

According to Prabhupada’s teachings, women are naturally meant to be subservient — customarily, they should stand behind men in services and obey their husbands. Records of his teachings, which western devotees will deny, report that he used to say things to the effect of, “The only two things that sound good beaten are a drum and a woman.”

Physical abuse is officially shunned by ISKCON, but submission of women is viewed as part of their duty in serving Krishna.

“I personally like it. It’s just the culture,” says Pancha-Tatva, “Point is, everybody has their position. I don’t mind cleaning the house and cooking. I do it out of love.”

Tales of a Kid Devotee

After Prabhupada died in 1977, ISKCON was thrown into chaos. Eleven ‘gurus’ who had spent most of their adult lives living a sequestered life within ISKCON were left to take over the movement and fill the leadership vacuum.

During the 80’s many of them were thrown in jail for everything from conspiracy to commit murder to drug smuggling and fraud.

Lakshmi Keyes, is a Boulder massage therapist who spent most of her childhood at New Vrindavan, a sprawling ISKCON estate in rural West Virginia.

The New York Times once referred to New Vrindavan’s ‘Palace of Gold’ as the “Taj Mahal of the West.”

In it’s heyday in the 1980’s New Vrindavan housed one third of all U.S.-based ISKCON devotees and had thousands of tourists visiting each year.

Sexual, emotional and physical abuse of devotees, particularly children, was rampant at New Vrindavan, but because of fear of being characterized as a cult, it took years for these problems to be addressed within the community.

Adult supervision at New Vrindavan was seriously lacking — one kid died drowning in a lake, two others suffocated in an old refrigerator, and many more were abused and neglected.

“I was raised to be detached — they believe human emotion is material. My whole life (since leaving New Vrindavan) has been a constant struggle to heal myself,” says Keyes.

Like all of the children there, Keyes was raised separately from her parents in an ashram segregated by sex. Her days began at 3:30 a.m. with a cold shower and a walk through the dark to a temple thirty minutes away, for morning service.

After cleaning and a meager breakfast — a full four hours after they awoke — the children would go to school, which lasted three hours. The subjects included basic math and reading, but mostly study of evocative Vedic texts.

After school the children worked cooking, loading wood for the furnaces or picking herbs.

Older children, like the adults, did sankirtan, dubbed ‘scamkirtan,’ by jilted devotees, which is distributing Krishna literature, or at that time, knock-off secular paraphernalia such as snoopy stickers, on the street for money.

After an early dinner the children would go to bed when it was still light out, which Keyes says, “was torture as a kid” although her early bedtime was the least of her worries.

Being deprived of the ability to form close relationships with adult caregivers, and enjoy the typical support and encouragement that would entail, caused major trauma to her psyche.

Keyes was plagued with nightmares throughout her childhood. In the superstitious world of ISKCON, she was tagged as being haunted because of them.

Once, she says, she played the part, acting possessed, jerking around and moaning, scaring another girl. The prank got her a nasty beating from her teacher and a night of isolation in a dark mud basement as punishment.

In 1986 when her father decided to leave New Vrindavan to establish a temple in Minneapolis, Keyes, twelve at the time, begged to go with him — there was no hope of running away from rural New Vrindavan on her own.

Even ‘karmi’ locals looked onto devotees with distrust and referred to Krishna kids as ‘hairy critters’ so getting help from the local community seemed unlikely.

Keye’s father granted her wish, but the move didn’t improve her life overnight. At first, it was difficult for her to understand and fit into the ‘Karmi’ world — TV captivated her, her K-mart threads boggled her and she clamored to grasp the culture of her ‘karmi’ peers.

A few years later, Keyes moved to Boulder with her father, who established a temple on Pleasant Street.

Keyes, who herself took up with a misfit ‘gutter punk’ crowd as a young teenager says, “I feel sorry for the kids being attracted to it (ISKCON) through straight-edge. They’re brainwashed to believe they’re not brainwashed.”

Like many early members, Keyes whole family eventually ‘blooped’ — Hare Krishna terminology for dropping out of the movement.

Despite her rejection of the religion, Keyes, still plagued by nightmares, will sometimes wake up the night and scream out, “Krishna!”

The Message in the Music

New Vrindavan leader, Swami Bhaktipada Kirtanananda was expelled from ISKCON in 1987 by the Governing Body Commission (GBC) and received a twenty-year prison sentence for his role in the murders of two ‘fringies,’ and for racketeering and copyright violation.

For a while New Vrindavan devotees took instruction from Kirtanananda from jail, until they too ousted him in 1993.

In July of this year the New Vrindavan was re-admitted to ISKCON, but the GBC plans to keep a close eye on activities there.

One major change is that New Vrindavan has sold land to devotees enabling them to establish their own farms or businesses, and children have the option of attending public school.

Despite the efforts of the GBC, scandal continues to haunt ISKCON. The Denver temple has been investigated for child molestation as well as the Dallas and Los Angeles temples.

A former LA-based devotee working in the nursery was slapped with 99 years in jail.

Hundreds of lawsuits have been filed against ISKCON, from people claiming they were sexually or physically abused as children in the gurukulis, scammed by a devotee, or their teenage children hidden away at the temples. Some parents went as far as hiring professional ‘reprogrammers’ to try and sway their kids away from the movement.

A little over a year ago there were charges of boys being molested at the Ljubljana temple in Slovenia.

The internet has proved to be a good resource for ISKCON to grapple with its problems worldwide. Inter-ISKCON bulletin boards feature debates on whether criminal charges should be brought out in the open, at the risk of scaring off new devotees, or aired so that ISKCON can no longer be accused of being a cult, sweeping its problems under the proverbial rug.

What do Karmi folks think of their kids joining ISKCON these days?

“My family is tolerant. It’s not exactly what they had in mind for me,” jokes Swanson, “but, they’re happy I’m not in jail.. You know how parents are — if you’re happy they’re happy.”

In the spring, the Gopals and Swanson, with his wife-to-be, plan on re-establishing Boulder’s Krishna temple, after they all return from trips to India.

In the meantime, devotees will be conducting Sankirtan in Boulder, though some say, despite its young population, Boulder folks are a tough audience — they don’t want to hear the spiel.

The hope is that they will find a college student to head up a CU Krishna club, which would enable them to distribute Krishna literature on campus.

Gopal and Swanson are unsure as to whether they might start a Krishna-core band to lure in new devotees.

“At first I was quite determined that I was going to start a hard-core Krishna band (when he joined ISKCON),” says Gopal.

“But I got engaged in other things. I started doing Sankirtan full time, and I found I wasn’t hankering for that. I could see doing it for Krishna and liking it, but there’s also some things I don’t like about it, you know, late nights, and the association.

Sometimes people don’t want to hear your message, they just want to hear you play loud music.”

END

Recommended Books on the Hare Krishnas

For those interested in cults and crime the following books (affiliate links) may be of interest:

Monkey on a Stick: Murder, Madness and the Hare Krishnas — a compelling true-crime style exposé of ISKCON and New Vrindavan in the 70s and 80s.

Betrayal of the Spirit: My Life Behind the Headlines of the Hare Krishna Movement — first person account by an ex devotee. Illuminating but rather devoid of personal responsibility for putting a good spin on abuse.

Train Wrecks and Transcendence: A Collision of Hardcore & Hare Krishna — A first-person memoir of krishnacore musician, Vic DiCara (aka ‘Vraja Kishor das’), who played in bands such as Shelter and 108.

Krishna’s Punk: A Parent’s Journey — A companion book to the above book. Vic Dicara’s father, Victor Leo DiCara recounts witnessing his son getting sucked into the life of a full-time Hare Krishna monk and punk musician.

Postscript

It seems the Denver temple is still going and if this promo video depicts reality, they are still seemingly having success recruiting young people.

From what I can gather devotees, Madan Gopal and his wife Pancha Tattva are now at a Hillsborough, North Carolina temple called New Goloka.

Ex-Krishna kid, Lakshmi Keyes is now known as Ambujam Lakshmi Keyes and lives in an ashram in Kerala, India. The name Ambujam was given to her by Amma, the ‘hugging saint,’ of whom she has been a devotee for over twenty years.

In 2005 ISKCON reached a $9.5 million dollar settlement with children who had been abused in their temples.

There were many related cases that were pretty wild, such as this one that made it to the Florida Supreme Court.

Today most of the information on the murder and child abuse scandal can be found on ISKCON’s own website. I interviewed ISKCON’s communications director for another article who said increased transparency was the goal.

He highlighted a shift in their recruitment practices.

Today, American Krishna temples aim to attract more conventional Hindus, usually Vaishnavists, to their pujas. In the U.S. they are usually first or second generation South Asian immigrants who lead regular civilian lives and visit the temple weekly or on special occasions.

This shift has helped many U.S. Krishna temples to remain solvent and it means there is not such an internal push to urge congregants to give up all their worldly possessions and become full-time devotees.