A once-popular underground drug, GHB is also used to treat a range of legitimate health issues, such as sleep disorders, anxiety, and opioid and alcohol misuse disorders.

In 2000, legislation making it a Schedule I substance was rushed through and signed into law with lots of hype and little scrutiny. It also remained a schedule III drug.

The unusual ‘double classification’ permitted it to simultaneously be made available on the market as a pharmaceutical drug.

Over twenty years later, the drug repeatedly described as a ‘fatal’ in the press is prescribed to children.

When it was sold in health food stores, the cost of GHB was pennies per dose. Today, a monthly supply can only be purchased from one company and costs patients nearly $6000 per month.

cover story, Boulder Weekly, 2000

cover story, Go-Go magazine, 2000

Go to a bar, a rave or just hang out on the street and you’ll come across somebody sipping an innocent-looking beverage, but getting a guilty high.

Despite a frenzy of media reports warning about the dangers of GHB, it’s not just serious drug connoisseurs experimenting with it — college party-goers have discovered it as a way to get ‘drunk’ without a hangover, well-versed advocates use it daily as a form of self-medication, people in the pornographic film industry use it for its prosexual effects during shoots, and in its darkest application, rapists discovered it as a way to render victims helpless by intoxicating them without their knowledge.

Politicians Killing the High

A popular underground drug, GHB is also known, according to police, as ‘G,’ ‘Liquid Ecstasy,’ ‘Vita-G,’ ‘Georgia Home Boy’ (pointing to its early use in the south), ‘Grievous Bodily Harm,’ ‘Easy Lay,’ ‘Somatomax,’ and ‘Scoop,’ among other names.

Its recreational use was first noticed by authorities on the US coasts in the early 90s, predominately in the rave party scene. Its use throughout the country steadily increased throughout the 90s, but President Clinton finally dampened GHB users’ high Feb. 18 when he signed House Bill 2130, classifying GHB as a Schedule I drug, the same category as heroin and cocaine. The bill also declared Ketamine (or ‘Special K’), an animal tranquilizer, a softer Schedule III drug.

In Colorado, police didn’t become aware of GHB use until the latter part of the 90s. Melanie Rhamey, Crimes Analyst with the Boulder Police Department, says they began to see GHB cases in 1998.

While some states have already passed laws scheduling GHB as an illegal drug, in Colorado it is considered a ‘gray-market’ chemical, meaning it can not be manufactured, sold, or promoted, but cops can’t haul people away for simply having it. When the new law goes into effect Apr. 18, merely possessing GHB or its chemical cousins could land users 20 years behind bars and up to a million dollars in fines.

Part of the appeal for recreational users was that GHB was easy to buy or make. The chemicals are household products, available at hardware stores — your average chemistry student can whip up a batch within minutes.

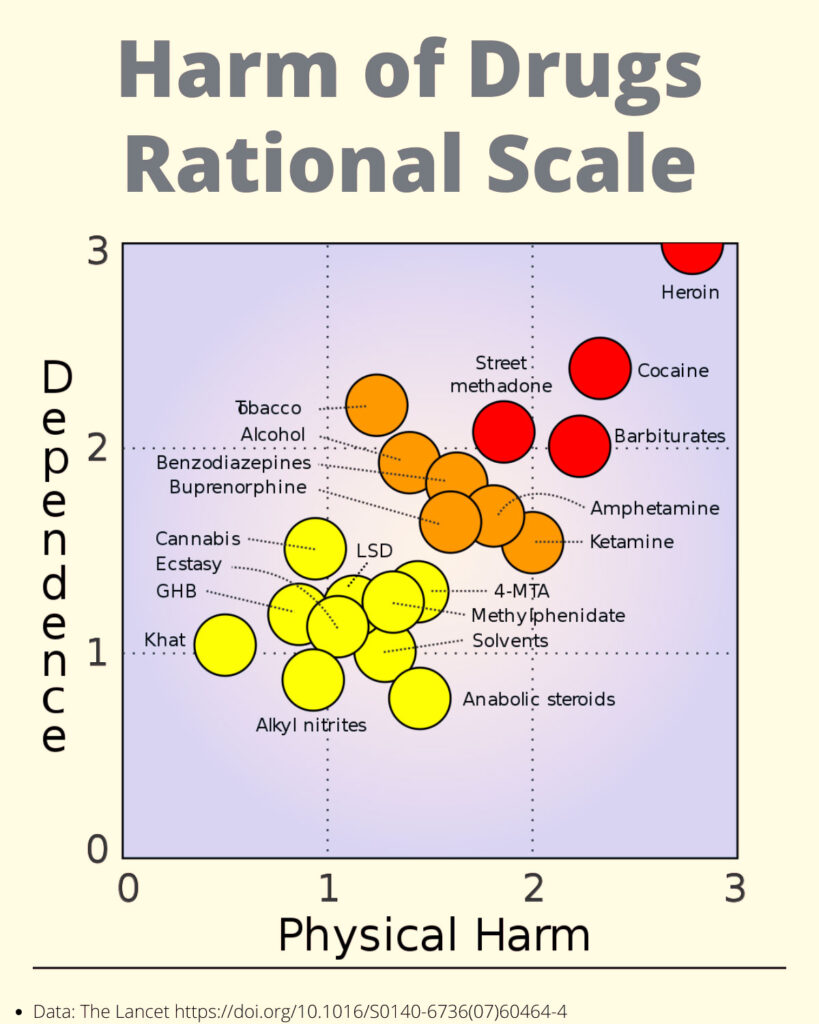

The Rational Scale of Harm of Drugs, developed by U.K. researchers, indicates GHB is less physically harmful and addictive than marijuana and legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco.

Until the recent crack-down, “chemistry kits” to make GHB were widely available on the Internet. The kits contained raw materials and instructions, and were air-mailed to clients within a matter of days. The distribution of kits was essentially a legal loophole, insurance against prosecution for selling and promoting GHB.

GHB advocates consistently warned against trying to make it with unknown grades of chemicals that might have been included in some of the kits — they said only very pure medical grades of chemicals should be used.

Now those who are still compelled to try and manufacture GHB will only be able to easily obtain low-grade chemicals, meaning future concoctions of GHB may be even more dangerous.

(Editor’s note: Even now GHB precursors are sold on Amazon disguised as cleaning products, such as this conspicuously expensive ecological ink cleaning product.)

G Whiz: Medical Use of GHB

Dr. Henri Laborit, a French researcher, discovered GHB (gamma hydroxybutyrate) in 1960 in an effort to synthesize a chemical mimicking GABA, a naturally occurring chemical in the body. Laborit found GHB useful for the treatment of sleep disorders, as an anti-aging property, to aid childbirth, to combat muscle deterioration, and aid sexual dysfunction and depression, among other applications. He was reported to be a daily user himself, until dying at the age of 91.

Prior to 1990, GHB was sold in US health food stores as a natural steroid alternative for its ability to increase pituitary growth hormone production experienced in deep sleep. Although this process isn’t fully understood by scientists, Japanese studies conducted in the 70s indicate that GHB burns fat and increases muscles when used in conjunction with heavy workouts. Because of its ability to produce growth hormone, which naturally declines with age, GHB has also been touted as an anti-aging chemical. It was only after GHB was outlawed for retail sale that its use in the party scene escalated.

A Boulder police officer, in District Three on The Hill, said she has come across several cases of students using GHB. One Friday night, she said, a young man who told her he prefers GHB to alcohol took four times the suggested dose and experienced convulsion-like muscle spasms. She reported that despite side-effects, he fully recovered, as did the other users she has encountered. Other symptoms of overdose are vomiting and unarousable sleep.

Despite the purported harmlessness of GHB when manufactured and used correctly, it can turn deadly when mixed with alcohol. Even pro-GHB literature warns against drinking alcohol while using GHB because they are both central nervous system depressants, which, when used in tandem, can shut down the body’s vital functions. GHB was reportedly found in the body of River Phoenix when he died at a Los Angeles nightclub — a report that many later disputed. Yet among college students, combining alcohol and GHB is common — reports abound of people guzzling GHB when they are very drunk, mistaking it for water despite its salty taste.

Advocates say GHB has been demonized in the press because of such irresponsible use.

“Our society has become so immune to alcohol,” said GHB user Anne Sheila Benetto*. “It’s the main reason people get sick when doing G. I’m a G purist. It irritates me when people mix it with stuff. When people don’t take it intelligently, I end up having to take care of them.”

Tim McFadden, a detox counselor at the Boulder Alcohol Recovery Center, said that in his ten-year drug-counseling career, he has never had an admittance of a GHB user for detox. “It’s out there but it’s an itty-bitty microscopic problem compared to alcohol abuse. It happens to be the drug of the day.”

Trading in the Prozac for GHB

It’s two AM and 48-year-old Rem Selnick* is mixing chemicals from plastic bottles marked “Keep out of reach of children.” As he pours the main ingredients to make GHB together into a bowl on his bathroom floor, a reaction reminiscent of a fourth grade science experiment occurs.

A hissing sound is created as the chemicals foam and bubble up. Selnick adds water to the concoction, then pops the clear, dense liquid into the microwave for six minutes. He’s just cooked up a liquid concentrate of GHB. A computer screen illuminates the room as Selnick pours the liquid into a glass of orange juice and begins to sip casually from it.

Selnick, the owner of a computer programming company, has long believed that adults should be permitted to alter their consciousness in any way they choose, provided they aren’t harming anyone. After being busted for cocaine possession and put on four years probation, Selnick has used GHB daily.

Selnick considers GHB medicine and says it has helped him in innumerable ways — it has made him more sociable, improved his sex life, helped him sleep, and cured what he has dubbed ‘Probation Stress Disorder’. Since it can’t be detected in routine urine analysis after a matter of hours, it is one of few only recreational drugs he can enjoy without getting in trouble for violating the terms of his probation.

When on GHB, he said, “You feel dizziness, like drinking, but different. You’re in a good mood, worries and concerns don’t get to you. It effects the way light looks. It makes the skin feel very good. It’s hard to have negative thoughts on GHB. It would be a more peaceful world if everyone did it.” But, he added, “Like any other drug you have to do it responsibly.”

Selnick said before he took up GHB he drank a quart of vodka a day.

“It is the one and only substance I hold responsible for allowing me to quit drinking. Four years — I haven’t had a drink.” He also credits it with allowing him to abandon his 25 year cocaine habit — something he said he has no desire to do, but is being forced to do by the state. This, too, he said, “would not have been even remotely possible if it wasn’t for the G. GHB helps on a wide panacea of levels.”

Selnick isn’t worried about side effects from GHB. He claims his psychotherapist and his physician, unaware of his GHB use, haven’t noticed any usual health problem and report that he is in good health. The only negative thing about GHB, he said, is that it impairs his driving as if he’s been drinking — a problem he has resolved by simply not driving while G’ed up.

Benetto, the eighteen-year-old GHB user, said she takes GHB an average of three to four times a day.

“I like to take it at work because it makes me sociable and happy. I’m a really tense person and it just helps me relax.” Because of GHB’s muscle building properties, Benetto said she can eat whatever she wants and stay in shape.

“I have a good body, and I do no exercise. I’m skinny and I have good muscle tone,” she said. “Genetically, I shouldn’t have this body. I know it wouldn’t be this good if I didn’t do G.” Although she’s mostly a daytime user, Benetto will also occasionally take GHB if she only has a few hours to get a night’s sleep. Since it takes users immediately into a deep sleep, she reports she wakes up feeling good.

Milo Delph*, a computer systems specialist with a chemistry degree, uses GHB to self-medicate his Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). When he was fourteen he started using cocaine to help him stay focused and alert for school.

“All of a sudden the fog would just lift. I could think like a normal person. I’d be able to read a book and finish a page without forgetting what I just read. Of course, it’s an exceptionally detrimental drug for a fourteen year old.”

It wasn’t until 1995, when he was twenty-five, that Delph finally was diagnosed with ADD. He was prescribed amphetamines, Xanax (an antianxiety drug), and Paxal (an antidepressant), which he said started a vicious pill cycle that made him constantly feel edgy.

“It got to the point that it was very bad,” he said. “Finally I discovered GHB.” After reading up on it, he quit the prescription drugs, learned how to make GHB, and began using daily, a switch that he claims allows him to function normally.

Seventeen year-old Juan Carlos* relates a similar path, but in his case, he suffered from depression and was prescribed Prozac. He said his psychiatrist doesn’t know he stopped taking the Prozac, but he has observed smugly that his treatment seems to be working.

Carlos purchases his GHB by the liter for about $40 or $50. Like Delph, he takes a relatively large dose of GHB in the morning and then follows it up with three to five milliliters up to 15 times a day. To pay for his own stash, he makes a profit reselling it for $100 a liter to former alcoholics, weight lifters, and even bartenders and shop owners at well-known Boulder establishments.

Now that these regular users are going to have difficulty obtaining the ingredients to make their chemical panacea, what do they plan to do? Selnick said even though the new law bans all of GHB’s precursor chemicals, he’s in the process of doing chemistry homework to find new GHB precursors that he hopes the DEA hasn’t discovered yet.

The Great GHB Debate

Behind the media reports is an intense GHB debate comprised of two very vocal opposing factions — on the one side is the FDA, DEA, and families whose loved ones reportedly died of GHB overdose. This is the group that has conducted a public awareness campaign and is responsible for getting GHB made into a Schedule I drug.

On the other side of the debate is a much smaller group of doctors, researchers, and GHB users, including narcoleptics, who are sometimes prescribed GHB to treat their debilitating daytime sleeping disorder. This group claims GHB is an exceedingly safe and useful substance that has been banned for the benefit of pharmaceutical companies, who they say are intrinsically intertwined with the FDA. They point out that the mainstream press often refers to GHB as a ‘designer drug’, but it is a natural substance found in meat and vegetables and every cell of the human body.

Central to the debate is the case of Hillory Farias, a seventeen-year-old La Porte, Texas, girl whose 1996 death was attributed to GHB overdose. Before the Farias case, no death had been attributed exclusively to GHB ingestion alone.

Farias died in her sleep after going to a dance club one night. No cause of death was able to be determined until a sheriff received a tip about a new underground drug called GHB from the Houston Police Department. An autopsy showed Farias had 27 milligrams of GHB in her system. Police determined that her drink must have been spiked with GHB at the club, causing her to die. In reaction, the Farias family rallied against GHB, seeking to inform the public about the dangerous new drug.

Dr. Ward Dean, co-author of ‘GHB: The Natural Mood Enhancer’, describes GHB as “one of the most useful substances known to man.” He is so confident in GHB and its precursor chemicals’ safety that he gives it to his kids to help them sleep.

After studying the autopsy report, Dean and his team say GHB had nothing to do Farias’ death. First, the amount of GHB found in Farias’ body isn’t even enough to get someone high.

In clinical studies, rats are regularly given many times that amount of GHB without dying. Narcoleptics use much higher doses of GHB daily without any reported side effects and three grams of GHB is typically prescribed to induce sleep. They also point out that Farias died in her sleep many hours after getting home.

Since GHB is a fast acting molecule, any effects from unusual toxicity would have showed up within an hour, they say. GHB overdose causes deep sleep within minutes, but Farias was able to say goodbye to her friends, get out of the car, get inside her house and climb into bed on her own.

Also GHB is naturally found in the blood post-mortem, says Dean. Up to 168 milligrams have been found in the blood of cadavers that had not ingested any GHB. Dean believes that that body can produce huge amounts of GHB at the time of death as a way to try and protect the brain and organs from low oxygen levels, thus essentially any death can be attributed to GHB ingestion if that’s what investigators are seeking.

Dean and his team say the coroner eventually determined that Farias suffered from a congenital heart disease, and died as the result of a blood clot. Nevertheless, the title of the bill that President Bill Clinton signed is officially called the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act (although neither of the girls were sexually assaulted).

In Samantha Reid’s case, she died the day after GHB ingestion. The death was blamed on GHB, although the drug leaves the body within a matter of hours. Reid’s parents were conspicuously absent from the list of people who testified in support of the bill named after their daughter.

Lack of Quality Control

The potency of street GHB varies widely, what may be an adequate dose with one batch could be too much with another. When produced in clandestine laboratories, it can also contain undissolved toxic chemicals. Even with pure GHB, a small amount will bring the desired effect — if a person takes too much they may get sick or fall into an unarousable sleep. Most users measure their doses by ‘caps,’ referring to the tops of plastic bottles from which many drink their concoction. Only one or two caps are necessary, but at a party it’s easy to be inattentive to how much one is ingesting. Some thrill seekers, unaware of the correct dosage, add large amounts of GHB to drinks as if it was alcohol, only to pass out or end up in hospital.

Since high doses of GHB induce very deep sleep, involuntary twitches and comatose-like sleep can occur. Yet some say even overdoses cause no lingering problems for victims. Cases have been reported where a GHB user ends up in the emergency room and pronounced comatose, only to wake up feeling well a few hours later, despite hefty medical bills. Others aren’t so lucky according to the Drug Enforcement Administration, who has attributed 45 deaths to GHB. According to Benetto, caffeine is a good antidote to GHB overdose. She carries around No-Doze tablets as a precaution.

“We’re worried the public is misinformed,” said Dr. Frank Daly a toxicologist with the Rocky Mountain Poison Center, which received 36 calls regarding GHB in 1998. “We’ve had problems. People think it’s good for them so they take a lot.” He says he’s had cases where parents give it to their kids, thinking that since it’s a nutrient, no amount is too much.

Alternative health practitioners who are proponents of GHB point out that in Europe, a GHB product called Alcover is prescribed to lessen withdrawal symptoms and cravings for alcohol and opioids. It’s also used as a sleep aid, and as an aid in childbirth for its ability to dilate the cervix and relax both mother and child.

In North Africa and Latin America it is used as a low-cost anesthetic agent. In the US it was also once used as an anesthetic, but doctors found it didn’t last long enough for many procedures.

There are currently 15 product investigation applications for GHB pending with the FDA. These ‘Investigations of a New Drug’ (INDs) are requests for further studies of GHB’s usefulness in an array of disorders, including high cholesterol and Parkinson’s disease.

One of GHB’s main benefits in medicine is that when manufactured commercially and used correctly, it is non-toxic. In fact, “Table salt is more toxic than GHB,” said Dean.

Presently, U.S. doctors are permitted to prescribe GHB in experimental research, testing its usefulness in the treatment of narcolepsy.

A report put out by the California Department of Health Services in 1992 inadvertently gave GHB proponents some of their best arguments. Their findings are covered in two pro-GHB books (affiliate links):

Better Sex through Chemistry: A Guide to the New Prosexual Drugs & Nutrients

and Dr. Ward Dean and coauthors’

GHB: The Natural Mood Enhancer.

Though the California report said GHB has tremendous potential for abuse because of its availability and the pleasurable feelings associated with it, they added, “There are no documented reports of long-term [injurious] effects. Nor is there evidence for physiological addiction.”

“The government’s real problem with GHB,” says Dr. Dean, “is that it makes people feel good.”

A Rapist’s Weapon

In 1997, Boulder police traced several sexual assaults to The Foundry, a local bar, where women suspected they were given drinks spiked with GHB. The typical scenario, said Detective Chuck Heidal, is that a woman wakes up in a strange place, and will report that she only drank a little alcohol, and then all of a sudden went in and out of consciousness, or cannot recall the evening at all after that.

It’s not only college students who are drugged and then sexually assaulted. Kate Feeny,* a professional woman in her mid-fifties, said she didn’t realize she had been raped until weeks after she had gone out on a blind date arranged through the Boulder Daily Camera personal ads. Feeny felt comfortable meeting the man — they had a long phone conversation beforehand and found they had some things in common.

When they got to the crowded restaurant, Feeny’s date went to the bar and got drinks for both of them. As he handed her the cocktail he warned her that “they don’t make them very good here.” She noticed the drink was a little cloudy and tasteless, but it had never occurred to her that he could have put drugs in the drink.

A regular social drinker, who says she’s well aware of her limits, Feeny had one more drink over dinner — the second one, she reports, was brought by the waitress and tasted normal. Over dinner, Feeny’s date leaned over and kissed her twice, testing, she says, to see if the drug’s disinhibiting effect was working. After dinner she went to his house, where he suddenly emerged from the bathroom naked. The details became fuzzy after that, she says, though she knows they had sex twice. Feeny says she had no will to react as she normally would. “I wasn’t attracted to him; I wouldn’t have gone to bed with him.”

The next morning Feeny had a headache and felt disoriented, but she didn’t realize she had been drugged until weeks later when she spoke about the incident to a friend and the details came together. She then realized the whole incident was premeditated — the man knew she had an important public appearance the next day, and would not be able to report the crime before the drugs left her body. Feeny doesn’t blame the drug for her bad experience. “Rape is rape whether they use one drug or another. It’s the way it’s used, it’s the intent.”

Sex crime experts say because of the shame felt by rape victims, and the lack of memory around drug-induced rape, the actual numbers of GHB-related rapes are probably much higher.

“Date rape drugs can be just as dangerous as a gun or a knife. It makes it easy for the rapist to commit their crime,” said Gail Abarbanel, director of the Rape Treatment Center at UCLA. Abarbanel and her team developed a line of educational pamphlets about drug-induced date rape for students.

Even when sex crimes are reported and there is physical evidence, assaults can be difficult to prove when victims do not remember details. Rapists have gotten away with their crime in Boulder by simply claiming the sex was consensual.

Toxicologist Daly said the only confirmed reports of drug-induced rape he has come across involve Rohypnol, a chemical cousin of GHB available in pill form.

Rohypnol, or Flunitrazepam, is usually smuggled from Mexico, where it is used as a pre-anesthetic agent. While Rohypnol (“Ruffies”) is a tasteless pill that can be dropped into a drink and cause memory loss for a significant period of time, its use is not as prevalent as GHB in Colorado.

GHB resembles sea water in taste. Regular users say it’s hard to imagine that someone could unknowingly ingest it because of the taste, but in sweet drinks it’s hardly noticeable, and the combined effects of the alcohol and GHB will cloud much more than a drinker’s sense of taste.

Foundry general manager Stan Craig said that because of their GHB incidents, they now have a sign in the women’s bathroom warning them not to take drinks from strangers or leave them unattended.

“Since last spring we’ve educated our clientele. This is something we want to prevent.”

Additionally, bouncers are told to observe couples leaving together to see that they are fully consensual. Though this is difficult to determine by a quick glance, if it appears that a potential victim is too inebriated to make an informed decision, the bouncers sometimes take down the license numbers of departing patrons to increase the chance that perpetrators will be discouraged. On occasion, they have even gone so far as to step in and put people in different cabs.

For official deterrence, prosecutors have been able to turn to the earlier legislation called the ‘Drug-Induced Rape Prevention Act of 1996’, which stepped up penalties for sexual predators who use date-rape drugs with the intent to commit a crime of violence. With the new law, officials have even more power to prosecute rapists using GHB as their weapon of choice.

Police say that if a person suspects she has ingested GHB and was consequently sexually assaulted, they should report it within at least 12 hours in order to gather evidence of the drug in her body. Even if victims do not want to formally report the crime or have little evidence, police say it helps if they call headquarters and report it informally to help them establish sex crime patterns.

Is GHB too Good to Be True?

According to the rule of thumb that says anything that makes you feel good is bad for you, GHB ought to be awfully unhealthy. Some users suspect it could have an undetected downside.

“I do worry about long-term side effects,” said Benetto. Since the substance has only been around thirty years, she said, she tries to compare possible side-effects with friends’ experiences — if she wakes up with stiff joints, she will ask other G users if they have the same experience. Still, she’s willing to risk the unknown for the benefits she experiences. “[GHB] seems almost too good to be true. It’s the perfect drug.”

McFadden, the substance abuse counselor isn’t so sure. Though it may not be proven to be physiologically addicting, GHB may subtly hook users, he notes. Marijuana isn’t physically addicting either, he said, but in his professional experience, habitual pot smokers have a very difficult time kicking their habit.

And there are the uncertainties of using an unregulated substance, points out Devin Koontz, public affairs specialist for the Food and Drug Administration’s Denver office.

“Underground consumers don’t know what they’re getting. Even when they manufacture it themselves, it’s not under sterile conditions.”

That’s exactly why it should be legal, say GHB advocates — for quality control.

But, “It’s not a conspiracy to keep GHB from consumers,” responded Koontz. “US drug companies could lobby for it to be approved and market their own GHB if they thought it had potential on the prescription market,” he said.

Advocates repeatedly counter that it is too cheap to produce to be profitable for drug companies to fund the rigorous tests required by the FDA. Laura Bradbard, a Washington-based public affairs representative with the FDA, says, “That would be a financial decision of a particular individual or drug company, but the law still says that a drug product must be tested in humans and must be tested to prove efficacy and safety.”

Xyrem, a brand name GHB product to be used for the treatment of narcolepsy, has been approved for production, but special registration requirements outlined by the new law have narcolepsy patients worried that the costs to manufacturers of meeting the requirements will mean Xyrem won’t make it to the market.

Normally, to proclaim a substance a Schedule I drug, the FDA has to declare the substance medically useless and an unacceptable risk to public health, but they were able to side-step that requirement in the face of the dangerous nature attributed to GHB.

Andrew Baer, an MD with practices in Pennsylvania and North Virginia, specializes in holistic medicine and has written a number of articles on the benefits of GHB. He said he has written prescriptions for GHB for a number of medical problems, but that there are no longer compounding pharmacists (who make their own drugs) in his area to fill the prescriptions. And while they used to be able to occasionally get GHB from overseas suppliers, patients now face serving time behind bars for following doctors’ orders.

“The FDA and the DEA are eroding our freedom,” he said. “You’ve got a few cases of kids abusing it with alcohol and its use in date-rape, so we have to make a law. We have a nation of sheep. They don’t educate themselves. You got a problem, so legislate. It’s the American way.”

If that’s the American way, it works for those who have fought to outlaw GHB — they’re just glad it’s finally officially illegal.

END

* Not their real names.

→ See Goodbye Legal High: Death of a Party Drug on the Wayback Machine

Addendum — How GHB Went From Party to Prescribed Drug, Virtually Overnight

(Note to Editors: if you are looking for GHB story, I’m hot for it. Below is a compilation of notes highlighting my urge to go further down the rabbit hole.)

In the last twenty years I’ve witnessed the lassitude of the press and the power of spin when it comes to drug trends, health and pharmaceutical reporting through this story.

I, too, started out figuring I would be writing a story about a ‘dangerous new club drug’ but what I found simply did not fit the narrative. Luckily editors at alternative publications such as the Boulder Weekly, Go Go Magazine and High Times were open to a more nuanced drug story than the usual scare-mongering.

This story was cited by the Colorado Department of Health — public health officials were initially clueless about the GHB scene, or perhaps more accurately, it wasn’t enough of a problem to be on their radar. As a review of early articles out there show, few had actual user anecdotes, much less pictures.

I’d like to point out that since this article was written, I discovered there is an GHB overdose anti-dote out there: physostigmine. For some reason, this is a well-kept a secret, even medical literature.

Don’t Let the Facts Get in the Way of Spin

The vast majority of GHB pieces out there are characterized by lots of speculation, innuendo and sometimes willful disregard for the facts.

The Chicago Tribune article, “Natural Supplement or Natural Killer?” is a typical representation. The title suggests that GHB is a deadly drug, but falls short with examples.

At the end of the article, the lone ‘GHB-related death’ highlighted was a young man named Matthew Coda. The Trib reports that while he was said to have a GHB addiction he, “accidentally overdosed on other drugs.”

GHB had nothing to do with Coda’s cause of death, but in the absence of any real cases of GHB deaths, the reporter artfully spins it to make it appear that GHB was the real ‘natural killer.’

This Newsweek article begins, “On the street they call it grievously bodily harm….it’s a tragically accurate description.”

It goes on to attribute the 1997 death of fraternity student Benjamin Wynne to GHB. Wynne drank huge amounts of a variety of hard alcohol, including Everclear. His BAC was 0.588, which is considered a lethal dose.

As with similar cases, Wynne’s autopsy showed ‘traces of GHB’ because it is produced endogenously and naturally occurs in alcohol (scientists have now even discovered it in non-alcoholic drinks) .

GHB gave a new spin to the sadly common ‘frat boy dies of alcohol poisoning’ story. Immediately after Wynne’s death, local cops focused on what they saw as the real problem and filed 86 charges of illegal alcohol sales to minors in the Baton Rouge area.

The Newsweek article goes on:

“”We have no idea what it actually does,” says Dr. David McDowell of the substance-treatment-and-research service at Columbia University.”‘

Why would a doctor specialized in the field of substance treatment have ‘no idea’ what it does, when there were decades of published research and it was legally prescribed in Europe at the time?

Not only is GHB erroneously linked to deaths by other causes but its also implicated in sexual assaults, even with an absence of the advanced testing needed to correctly detect it.

“We have seen an increase in rape victims reporting… symptoms that go beyond a normal hangover,” says Columbus Ohio police detective Jay Fulton in one article. “These symptoms are typical of someone who has been drugged with GHB.”

Fulton, like many others who mention GHB’s ‘horrible hangover,’ was apparently unaware that GHB is prescribed for sleep disorders, aiding patients to get deep sleep. The fact that it produces no hangover is one of its well-known medical characteristics.

On a pharmaceutical drug review site of the drug, a 43-year-old Xyrem patient writes, “With Xyrem [GHB] I have no grogginess and wake up alert and rested. My Dr [sic] said it dramatically improved my “sleep architecture,” the amount of time I spend in the various phases of sleep. Can’t imagine living without it — just wish it was not so expensive…”

Other patients on the site write that ‘it saved their life’ it’s a ‘life changer’ and ‘they can’t imagine living without it’ because of how much it repairs their sleep.

Could it be that a victim who reports a bad hangover is actually hung over? In the absence of reliable date-rape testing for GHB (or, if available, tests conducted within the narrow time window before GHB leaves the body) in some of these cases, Occam’s razor would suggest the number one date-rape drug through the ages was the culprit: booze.

That is not to say that GHB can’t be used as a date-rape drug. It most certainly can, but the quantity needed would made a drink very salty. There are many cases where cops come up with theories and reporters run with it.

Many news reports also report seizures associated with GHB use, although multiple studies show it does not cause seizures in animal subjects, even at high doses, with laboratory rats enduring five continuous days of intravenous administration of 600 mg/kg.

The association of GHB with seizures has to do with mycological jerks caused by the anesthetic properties of GHB, which are incorrectly interpreted and recorded as seizures, even in emergency rooms.

Some journalists never realize that the ‘deadly street drug’ GHB and the highly sought-after sleep disorder medication sodium oxybate are exactly same thing: gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid (C4H8O3), four carbon atoms, eight hydrogen atoms, and three oxygen molecules.

At least one scribe out there has dutifully stuck to preferred narrative, reporting on the ‘fatal drug GHB’ but whose also reported on the ‘safe, life-changing medicine, Xyrem’ — all the while completely unaware that they are the same substance.

Further confusing the public is that authorities, reporters, and sometimes even scientists, use the term GHB (γ-hydroxybutyrate) as if it were synonymous with its precursor molecules GBL (γ-butyrolactone) and 1,4-BD (1,4-butanediol).

GBL and 1-4 BD are used extensively in industries such as agro-chemicals, cosmetics, and food flavoring. Educated users and doctors such as those I interviewed do not use the names of the substances interchangeably and they warn against using unsynthesized GHB analogues.

While GBL and 1,4 BD do convert to GHB in the body, the liability for abuse and health-related issues is higher because they are fast acting and more potent molecules. Still these precursors are considered non toxic to the organs and non carcinogenic.

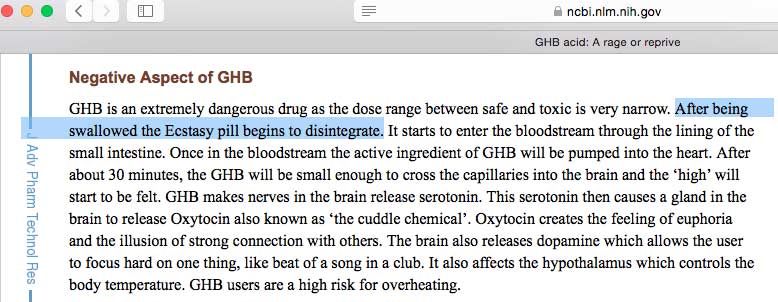

A published medical journal with incorrect information about GHB, confusing it with the stimulant, ecstasy.

Even published medical articles aren’t immune to misinformation. The above article ‘GHB ACID: rage of reprive‘ [sic] confuses the pill ecstasy with GHB, which is in no way chemically related, and goes on to describe the effects of that drug even down to the release of oxytocin, the ‘cuddle chemical.’

Typical GHB articles, admittedly including mine above, list supposed nicknames for the drug, including: ‘Liquid Ecstasy,’ ‘Georgia Home Boy’, ‘Grievous Bodily Harm,’ ‘Easy Lay,’ ‘Somatomax,’ and ‘Scoop.’

These nicknames got spread around in law enforcement press releases going back to the 90s and are still used in articles today.

Apparently readers are to suspend disbelief and convince themselves that young people today use the same drug slang as their raver parents in the 90s.

In truth, I never heard users call it any of these names but since every press release and government-produced drugs report repeated these supposed GHB street names, I figured then there must have been some truth to it. Maybe someone, somewhere calls GHB ‘Easy Lay’ and ‘Scoop,’ but the many users I interviewed were not among them.

Now older and wiser to police spin, I suspect cops made up some of the the names, at least, ‘Grievous Bodily Harm,’ as users I talked to didn’t feel it was harmful if used responsibly, the acronym (GBH) doesn’t even work and the term ‘Grievous Bodily Harm’ is frequently used among law enforcement. Hmmm…

In the article above I added the street names the police told me and added one I learned from users, ‘Vita G’ (although most just called it ‘G’). But as with a lot of common misconceptions about GHB, things get recirculated from the police to the press over a period of years until urban myths born at the official level are taken as facts.

An Anti-GHB Crusader

Ex cop and professional expert witness, Trinka Porrata, is likely the main source of the scary GHB descriptions that appear in article after article. She is cited in the Chicago Tribune article linked above about how deadly GHB is, even though it doesn’t mention one GHB death, as well as in most national articles and news programs seeking a pre-fabricated seductive scoop on ‘the dangers of GHB.’

Porrata is a retired LAPD narcotic detective, who later founded a non-profit corporation, Project GHB. She helped create comforting narratives with grieving parents looking for a boogeyman to blame for their child’s death, said ‘it’s made with floor stripper’ over and over in interviews, and began taking donations before becoming a hired gun in drug facilitated date-rape cases.

In the following video, Porrata makes an oft-repeated statement: “The primary ingredients (of GHB) are paint stripper, floor stripper, degreasing solvents.”

Her made-for-TV soundbytes about GHB being made with deadly chemicals have been repeated ad nauseam, but illustrate a lack of basic chemistry knowledge.

Ethanol (the active ingredient in alcohol) is also a good paint stripper — it’s equally true to say that beer is made with paint stripper as it is GHB.

Sodium hydroxide, a primary ingredient in soap, (and GHB, including the pharmaceutical product, Xyrem) is the ‘degreasing solvent’ to which she refers.

Google returns 94,000 search results for the term ‘GHB ‘s primary ingredient is paint stripper.’ Various versions of this statement made their way into the Congressional Testimony to outlaw GHB and were repeated over decades to the press. Hopefully they are aware the even more popular hygroscopic solvent — ethanol makes a great paint stripper too.

“This is the most dangerous drug I have encountered in 25 years as a cop,” Porrata continues in the TV interview (37:20)

To put that statement in perspective, consider that the CDC says 91 deaths a day in the U.S. are attributed to opioid overdose, making opioid-related OD’s the leading cause of all accidental deaths in the U.S., having long overtaken car accidents as the number one cause.

Alcohol is even more deadly: it causes an average of 261 deaths per day, according to the CDC. Among intoxicants, alcohol (which GHB can mimic in effect) remains the leading cause of ER visits. According to the CDC, 2,200 deaths a year are from acute alcohol poisoning.

By comparison, according to Porrata’s own website, worldwide a total of 226 deaths were speculated to have been associated with GHB in all of human history. Some of those listed were actually car accidents, drownings, suicides or otherwise tenuously linked to GHB ingestion. Two of the deaths are from 1948 (before GHB was synthesized in the lab). Though those deaths were attributed to the precursor chemical 1,4 butanediol, they still appear on her ‘GHB Death Count.’

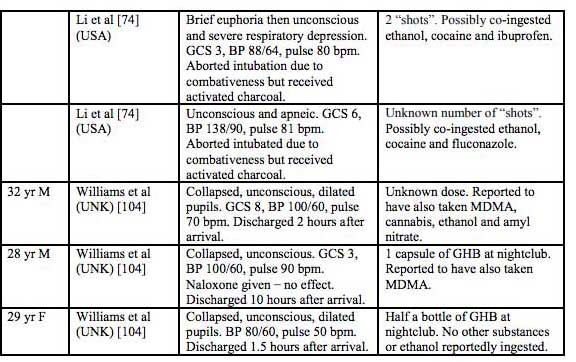

WHO data on GHB emergency department admissions highlights typical polydrug use and more aggressive treatment (intubation) in U.S. emergency rooms and typical recovery, including discharge of a patient that took ‘half a bottle,’ (one teaspoon is a normal dose), 1.5 hours after admission

“GHB isn’t included in any standard testing protocol and thus without specific knowledge that the person may have ingested GHB, testing isn’t likely to occur,” writes Porrata on her website.

This is true, the lack of a standard testing protocol can also mean that drug intoxication deaths and drug facilitated sexual assaults are just as easily misattributed to GHB as caused by them, especially because it is naturally present in all cadavers and in booze.

Porrata’s unscientific ‘GHB death count’ based largely on hearsay has been reprinted by newspapers worldwide. As it says on her website, the death, ahem, ‘statistics,’ “includes those picked up from newspaper accounts, coroners, law enforcement and as reported by family and friends.”

The DEA, for its part, puts the total number of U.S. GHB deaths at 72, with most being associated with polydrug use.

Among those whose death were dubiously blamed on GHB is former Mr. America, Michael Scarcella, who died while in hospital after receiving a beating outside a bar. Scarcella was diagnosed with a blood infection and pneumonia and died a few hours after admission. Porrata’s website nevertheless cites his death as a ‘GHB fatality’ because like other body builders at the time, he took GHB for its anabolic effects.

A lack of scientific credentials notwithstanding, Porrata is cited as an author on a study that appeared in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, which draws on the data from her specious ‘GHB death count’ above.

Among the professionals who put their credibility on the line by coauthoring scientific research with an anti-drug ex cop: Deborah L. Zvosec, Ph.D.; Stephen W. Smith MD; (both from the Hennepin County Medical Center) and Quinn Strobl MD.

Zvosec and Smith have published a number of research articles on GHB, including the paper, ‘Agitation is common in gamma-hydroxybutyrate toxicity’ which was soon thereafter called into question by other scientists who wrote, “the data the authors have presented from their observational study do not support their conclusion that agitation is common in people with GHB toxicity.”

But it is the number of research papers co-authored with Porratta that need more scrutiny.

As with many studies worldwide, deaths are attributed to GHB in ‘retrospective studies’ examining data of recorded deaths, even including information taken from news reports.

U.S. emergency rooms are more prone to intubate patients who arrive unconscious (or if they are ‘combative’ as in the graph above) which can lead to more complications. One person I interviewed for this story (which i didn’t include because I couldn’t verify his hospital admission) said after being found by a friend while passed out in a deep GHB-induced sleep he woke up in the hospital with an endotracheal intubation. He told me he suddenly awoke, pulled the tube out of his throat, disconnected his IV and snuck out of the hospital to avoid being presented with a large bill.

Spontaneous awakening and recovery from a GHB-induced coma is common. In a thirteen-year Swiss study, 77 patients admitted for GHB intoxication recovered and there were no fatalities.

Intubation is not a benign medical procedure. It can lead to puncturing of tissue in the chest cavity, damage to the vocal chords and mouth, injury to the trachea, fluid buildup and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). VAP occurs in 9-27% of ventilated patients and has a mortality rate of 50%. Doctors are even wary of putting COVID patients on ventilation because of poor outcomes.

In countries with non-profit healthcare systems, such as the Netherlands, intubation is not recommended as standard care for GHB intoxication and they report only 1.4% of GHB overdoses required intubation.

A three-year Australian study on treating GHB overdose found that not intubating patients lead to shorter length of stays and fewer complications.

Mackenzie Severns Rape Case

Although positioning herself as a crusader against both GHB and drug-induced rape, more recently Porrata (who lists herself as an expert witness on Linkedin) testified in a Peruvian court on behalf of a now convicted rapist, Vincente Pastor Delgado. (It should be noted that Latin American courts limit prosecutors’ use of expert testimony.)

The son of Peru’s former Justice Minister, Delgado was accused of raping a 15-year-old American study abroad student, Mackenzie Severns.

Thanks to the wealth of Delgado’s family, they were able to contract Porrata as an overseas ‘expert’ on date rape drugs to testify in the case, despite the trial taking place in a different language and cultural context.

Porrata claimed that because of a culture of ‘hooking up’ among young people, consent was implied — albeit nonverbally — by the victim and that she was simply embarrassed that Delgado told their friends they had sex, so she later claimed to be assaulted.

(An example of how many things can get ‘lost in translation’ when foreign consultants testify in criminal cases is evidenced in this video, where the key words, ‘hooking up’ don’t even get translated, likely because the translator didn’t understand the slang. The examination of youth ‘hook-up culture’ was central to the defense in this case.)

The victim, Mackenzie Severns, had her blood tested long after traces of GHB could possibly be detected. Peru has no emergency room testing criteria for GHB, so there is no way to know for sure if Severns was drugged. She testified that while a party, Delgado gave her sips from a bottle of Pisco. She then felt nausea and was in and out of consciousness for the rest of the night while Delgado assaulted her.

“I felt an inexplicable fear because I was a virgin and I had never imagined that my first sexual relationship was going to be like this,” she said in the original 2018 police report.

Other Questions of Credibility

It turns out Porrata’s credibility was called into question in a 2015 date-rape case before the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. In that case she testified for the prosecution, opining that the victim’s behavior was consistent with GHB intoxication, even though the state admitted there was no unusual level of GHB found in the blood and urine tests.

Per the appeals petition:

“The Court erred in allowing Trinka Porrata to testify as an Expert Witness on the issue of GHB Intoxication. The Defendant filed a “Daubert” objection to Trinka Porrata’s proposed testimony on the issue of GHB intoxication. The science behind her testimony does not meet the “Daubert” standard.”

Under cross-examination Porrata admitted that she had no peer-reviewed articles to back up her ‘expert opinion’ that the victim was drugged based on the drug analysis reports.

In the petition, defense lawyer, James T. Kratovil, characterized Trinka Porrata as a, ‘self made expert’ who used ‘junk science’ ‘based on anecdotal evidence.’

Blaming GHB in the Felica Tang Murder Case

In a homicide case Porrata testified for the defense in the case against Brian Randone. Randone is a pastor, ‘bible mime,’ and former reality TV contestant on ‘The Sexiest Bachelor in America.’

Randone was charged in the beating death of his porn actress girlfriend, Felica Tang. Police were so horrified by the crime scene and the severity of Fang’s injuries that they also charged him with torture.

Porrata testified that in her opinion Tang died of a drug overdose and that her over 300 wounds and badly bruised face were self-inflicted and all caused by GHB.

Self-injury and ransacking one’s own house do not appear on the list of possible side effects for Xyrem and other GHB medications.

In the CBS program, 48 hours “The Preacher’s Passion” about the case Porrata says, “I like to put people in prison. I like the sound of handcuffs, morning, noon or night, but I like for them to be guilty. But there just wasn’t enough there.”

Prosecutors thought they had a slam dunk case, but Randone was acquitted. As Randone said himself on 48 hours, “When the facts don’t fit your theory, change your theory to fit the facts.” He could have been describing his lawyer’s defense tactic.

One jury member said she was ‘haunted’ they simply didn’t have enough evidence to convict.

Whether it’s to convict or acquit, GHB is the perfect trial wild card to confuse any jury.

The GHB Project

Porrata is listed as the president and website owner of the GHB Project, which helped launch her second career as an anti-GHB crusader and expert witness. The last 990 filing available on Guidestar, from 2004, shows net contributions of over $54,000 and expenditure of over $61,000, with over $37,000 of expenditure listed as ‘other expenses.’

GHB Project’s lone board member is Elise Hagmann, a mother who believes her child died after his drink was spiked with GHB.

While some news articles state Kyle Hagmann died from alcohol poisoning, others say he took GHB to sleep sometimes. At first Hagmann believed that her son took the drug of his own free will, after a night of drinking.

After consulting with Porrata, Hagmann’s mother came to believe a narrative that better preserves Kyle’s purity: that his college dorm mate spiked his drink. She says the roommate gave Kyle a drink with the goal to knock him out so that he could have sex with a girl in the shared dorm room.

“Kyle was never involved with drugs and didn’t associate with people who were” write Tony & Elise Hagmann on Porrata’s website.

Hagmann’s death was attributed to an involuntary GHB drugging and published worldwide as such, although it was a fairly questionable story. If Kyle were a regular GHB user, as was originally reported, he surely would have recognized the taste of GHB in his tainted drink. No charges were ever filed against the roommate.

The Hillory J. Farias Case

The 2000 Congressional Bill, the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act was named for two teens who died after partying with friends.

What mainstream news reports fail to point out is that — despite the bill’s name — neither girl was sexually assaulted, nor was there even any attempt to assault them.

Although Farias still appears as a ‘GHB Death’ on Porrata’s website, Dr. Ward Dean disputed that Farias’ death was caused by GHB at the time because she continued normally with her evening after supposedly ingesting it.

According to her family’s Congressional testimony in support of the bill, after coming home from what was described as a ‘country western nightspot,’ Farias was lucid and acting normally the evening of her death after allegedly having her drink spiked with GHB.

GHB overdose causes incapacitation within minutes of digestion. Because she complained of a headache that evening, Harris County Medical Examiner’s Office first speculated that her death was caused by a cerebral hemorrhage.

After repeated postmortem tests over two months, the cause of death was finally attributed to GHB. The medical examiner said her blood contained 27 ml/L, which falls within the range of a typical postmortem concentration of GHB (people who did not consume the drug.)

Joye M. Carter, the Chief Medical Examiner in the district at the time, initially determined that she died of a brain hemorrhage. He said in his congressional testimony in support of the bill that,”The death of Hillary Farias is now one of many examples of the dangerous properties of GHB.”

In the question and answer segment he admitted that, “the blood level was low, by our forensic standards…” But, he highlighted that his office set a precedent when Farias’ death was ruled homicide due to gamma hydroxybutyrate toxicity.

(It was later noted during the Congressional meeting that alcohol is ‘of course’ the number one cause of accidental death caused by drug ingestion.)

What was never explained in the hearing is why her friends would have slipped Farias a drug in the absence of any intent to sexually assault her. Articles published at the time reflect how authorities were taken at face value.

One Time article published at the time says, “Police speculate that someone slipped the GHB into Farias’ soft drinks when she was not looking.” Never mind who it was, or what their motive was, or that Farias’ autopsy showed a normal endogenous amount of GHB.

Time-verified police speculation took the story to the big leagues, and there was never a retraction.

Ward Dean M.D. and Steven Wm. Fowkes wrote at the time that the coroner’s autopsy report was ‘pure fantasy.’

Soon after the Harris County Coroner’s office became mired in controversy for the mishandling of other cases, including cases in which those convicted were sentenced to life or execution.

There was never any correction about the true cause of death in the Farias’ case by the Harris County officials, and the case still appears as a ‘GHB death’ on Porrata’s website.

The Samantha Reid Case

Samantha Reid was the other deceased teen whose tragic death meant her name also got tacked onto the ‘date rape’ bill to reschedule GHB.

The following Associated Press article is titled, ‘Four Convicted in Date Rape Case.’ As with so many of these articles, it is referred to as a ‘date rape case’ in the title and ‘date-rape drug death’ in the lede, even though no sexual assault took place and there wasn’t even suspicion that there was ever an intent to sexually assault Reid.

Three friend’s of Reid were convicted for involuntary manslaughter and another on lesser charges, after one defendant confessed to spiking her drink with GHB.

The manslaughter charges were later thrown out in appeals court and then later reinstated by the Michigan Supreme Court.

A website created by Reid’s mother, Judi Clark, called GHBkills.com has been taken down and the Samantha Reid Foundation appears to no longer be active.

Some news reports said Reid died of asphyxiation. The group had also been drinking alcohol. It came out in trial that an unconscious Reid was also dropped on cement after her friends slipped on ice while carrying her to the car to take her to hospital.

Reid died 18 hours after the assumed GHB ingestion, long after the substance would have left her body.

Grindr Serial Killer Steven Port

It is repeated in the medical literature that “deaths attributed solely to GHB or its precursors are rare” nevertheless GHB continues to be blamed for deaths in high profile cases, leading to stricter legislation.

Authorities came under fire in the Steven Port case after they failed to recognize that a rash of killings of gay men in London were the work of a serial killer. As outlined in the BBC documentary, How Police Missed the Grindr Killer, the gay community put 2 and 2 together much quicker than detectives, who initially ignored their pleas to investigate if the killings were connected. There is an ongoing investigation into any negligence on the part of police.

One of Port’s victims, Jack Taylor, was found with needle marks on his arm and with a used syringe in the vicinity. GHB is not used intravenously by recreational users. Port did purposely leave bottles containing GHB near three of his victim’s corpses, along with other items, such as a suicide note on one victim, a tactic meant to mislead the police to believe they were accidental drug deaths.

In the trial it came out that Port drugged his victims with a variety of substances such as amyl nitrite, viagra, methadrone, GHB and crystal methamphetamine. The media narrative about the case focused on the missteps of the police but was very thin on technical details of the druggings or the actual cause of the deaths in autopsy reports.

It is presumed that Port did actually inject the victims with GHB, even though it historically is only used intravenously in surgical procedures or animal experiments. If the autopsies were made publicly available it would allay any concerns about the police erroneously blaming the deaths on GHB as coroners have historically done across the pond.

Much like in the U.S., several high-profile sensationalist cases were used to push through anti-GHB legislation increasing penalties on GHB possession in the U.K., despite a lack of hard evidence that GHB caused the deaths of the victims.

GHB was also blamed in the case of serial rapist Reynhard Sinaga. A Guardian article published at the time notes that no drugs were found at Sinaga’s house but says, “prosecutors insisted the men must have been drugged, probably with gamma-hydroxybutyric acid – commonly known as GHB – or something with very similar effects.”

Another Guardian article published the same day says, “Even at quantities as low as 1ml, GHB can render a person unconscious,” which is false. At least five times more than that would be needed to even feel the effects.

While there was plenty of evidence on trial implicating Sinaga in facilitated sexual assault there was never any proof provided that Sinaga used GHB to drug his victims. The only victim who had realized he had been assaulted by Sinaga at the time said he was very drunk.

Nevertheless, in the time since, GHB has been rescheduled to a Class B drug in the U.K., alongside amphetamines and cannabis. The legislation was pushed through by U.K. Home Secretary, Priti Patel, who has since been accused of corruption by using her position to arrange a sweet pharmaceutical deal for one of her political donors.

Patel is a former tobacco lobbyist and alcohol industry insider. Patel was forced to resign as International Development Secretary from Theresa May’s government for a secret scheme to channel UK foreign aid money to the Israeli army.

Blaming GHB for facilitated sexual assaults may make interesting headlines and usher in new legislation, but one published medical study found it is only implicated in .2-.4.4% of sexual assaults and even scolds the ‘sensation seeking media.’

“Our results do not support the widespread labelling of GHB as a date rape drug as the prevalence of GHB is much lower than of other substances used in sexual assaults. On the other hand, however, the possible risk of GHB in this regard should not be neglected. Nevertheless, over-sensitive and sensation seeking media reports focusing on the association of sex crime and GHB might be counterproductive and misleading as they turn the attention away from other substances that are often used in sexual assaults.”

Operation Webslinger

Operation Webslinger was a 2002 multi-task force sting operation that resulted in the arrests of 115 people in 84 cities across the U.S. and Canada for GHB.

The U.S. Attorney General’s press release sent at the time says, “Contrary to misinformation disseminated via the internet, the drugs targeted in yesterday’s arrests are extremely addictive and life-threatening.”

Although taken at face value by reporters, that statement directly contradicts current medical knowledge and decades of studies in multiple countries with one study by Lancet stating:

“Sodium gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) is a remarkably safe and nontoxic hypnotic agent which is reported to be free of addicting properties.”

Another study by the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry concluded, “No patient developed tolerance to the drug, and no serious side effects were noted.”

A study on the physiological effects of GHB published by the Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences concluded from their study that, “Tolerance did not develop and there were no serious toxic side-effects.”

The year of the largest GHB sting ever recorded was the same year that it was fully approved for use on the pharmaceutical market.

Pharma Execs Laughing all the Way to the Bank

What a few years earlier was available to anyone in health food store for pennies per dose, was made a schedule I drug, sending people to jail for long stretches for possessing a natural metabolite. In the end, the big winners were pharmaceutical executives.

Immediately after GHB was outlawed and users jailed thanks to the passing of the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act, one pharmaceutical company, Orphan Medical, was given exclusive rights to produce and market the drug, brand name, Xyrem.

In 2005, Orphan Medical was acquired by Jazz Pharmaceuticals, who dramatically increased the price of the already expensive drug.

Since it was approved, the cost of Xyrem has increased by an average of 40% per year and now costs at least $6,000 for a month supply. Overseas brand names of sodium oxybate include Alcover (Italy), Gamma-OH (France), Natrii oxybutyras Kalceks (Latvia) and Somsanit (Germany), all of which are far cheaper than Xyrem.

In 2017, a generic version was approved in the United States but it has not made it to market. There is a financial assistance program for patients although it appears that participation requires patient consent to revoke their privacy rights.

Jazz Pharmaceutical CEO Bruce C Cozadd has an estimated net worth of $116 million dollars and earns nearly 15 million a year as Jazz CEO according to a very unreliable website. It’s safe to say he’s comfortable.

Hillary Clinton who usually styles herself as a pharma industry foe, received the maximum contribution to her 2016 presidential campaign from both Jazz CEO, Bruce Cozadd, and its senior vice president, Robert McKague, shortly after they hiked Xyrem’s price 800 percent.

GHB was outlawed under President Clinton.

While anti-drug crusaders and the journalists who take them at their word continue to blame unconfirmed cause-of-death cases on GHB, narcoleptics and drug misuse disorder patients safely take up to ten grams a day.

Today, Xyrem/GHB, is considered ‘effective and safe‘, but it is so expensive that most patients who need it can’t afford it. Even in countries with universal health care some patients linger on the verge of bankruptcy to pay for their supply.