The Denver residential neighborhood of Sloan’s Lake in Northwest Denver has increasingly become a gathering place for homeless people.

Due to its distance from downtown, the demographic of homeless here includes those who want to avoid the downtown drug scene: veterans, former foster kids, senior citizens, the mentally ill and families.

—North Denver Tribune, October, 2003

“I pray to God every night that I don’t come out here and find someone floating face up in the lake,” ‘Little Mike’ Quintana, manager of Sloan’s Boxing Club said last week.

The statement turned out to be an eerie prediction. Two days later a body was found floating in the southwest corner of lake about 40 yards from the boxing club.

Tim, a homeless veteran was sitting at his regular park bench Friday afternoon in Sloan’s Lake Park when he noticed what appeared to be a pair of human feet sticking out of the lake. Upon closer inspection he realized it was a body, a fallen brother of the street. He asked the first person he saw with a cell phone to call 9-1-1.

The body was that of 50 year-old homeless man, George P. Rael. The Denver County Coroner’s office says the autopsy results indicate no foul play — he died of an accidental drowning. A toxicology report will be out later this week.

The homeless population around Sloan’s Lake is only a microcosm of the growing problem across the city. There are now 9,725 homeless people in Metro Denver according to a recently released report by the Department of Human Services.

By comparison, in 1990, Denver’s homeless population was less than 2,000 people. The circumstances of those facing life on the street today run the gamut from disabled vets like Tim, to the mentally ill, impoverished families, alcoholics and drug users and people who just ‘fell through the cracks.’

Neighbor’s Complaints

At a recent Sloan’s Lake Citizen’s Group meeting a few people complained about the numbers of homeless people in the park ‘nesting,’ as one person called it.

Some said the homeless people are drunk and rowdy and panhandle around the neighborhood. They asked then District 1 Commander Brian Gallagher what they could do about it.

“If there’s no other crime being committed, it’s not against the law to be homeless,” said Gallagher.

He added that Denver has no vagrancy or loitering ordinances. The police are only empowered to enforce aggressive panhandling.

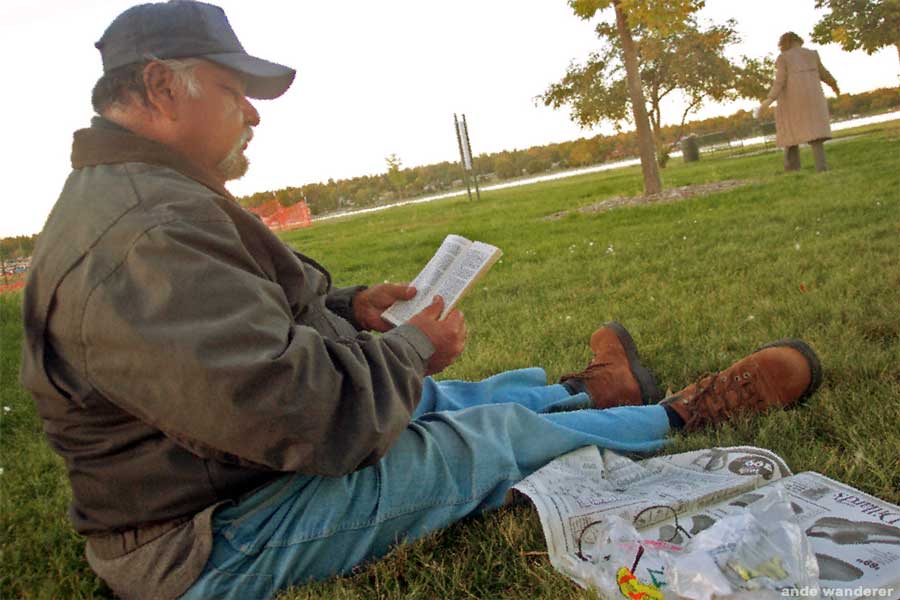

Dave Garcia reads a book as his girlfriend wanders around the park behind him

The Varied Circumstances of Homelessness

Dave Garcia became homeless just this year, when he was forced into early retirement and couldn’t find another job. His girlfriend became homeless many years ago after an accident resulting in a head injury that left her mentally disabled.

Perhaps the most notorious homeless person around Sloan’s Lake for frustrated residents is the ‘shopping cart lady’, who cusses at people and inanimate objects and whose random outbursts have alienated her even from other homeless people, who typically ban together.

Sarah is a teen who became homeless when she aged out of foster care.

Also residing in the park is eighteen-year-old Sarah who went straight from foster care to the streets. She bounced through eight foster homes in the last four years after her biological mom became a crack addict.

When she became of age, her government benefits were cut off and she joined her boyfriend, Eli on the streets. They sleep on a pile of rocks underneath a footbridge at the park, which at least gives them coverage from the elements.

Sarah is perhaps the most spooked by the recent death at the park — her trademark prop is a golf club she carries for protection.

Katherine, with her big blue eyes and mass of gray hair, looks like somebody’s affable grandma. At nighttime she sleeps at the nearby Brandon Theodora Home for Women and Children. During the day she packs up her belongings in plastic bags and walks to the park to sit and wait for the shelter to reopen for another night.

When asked how she became homeless she says simply, “I ran out of money. I’m a senior citizen.” She’s one of many at the park whose old age pension doesn’t come close to paying for even a studio apartment in Denver.

Two year-old Luv isn’t old enough to comprehend the sadness of spending her 2nd birthday in the park, with nowhere to call home and only dry cereal to eat. Under the care of her parents, Melvin and K.C. she has been bouncing from shelters to motels to the backyards of friends.

After exhausting their emergency vouchers for motels for the month, Melvin left his family at the park to try and get rehired at an old job last Monday. He said he’d return at 1:30 p.m. By nightfall he had not returned. In tears, K.C. put the warmest clothes on her daughter and began to try to figure out the safest place in the park to sleep.

John Parvensky, President of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless says the boom in homelessness can be attributed to obvious economic issues. The homeless have become more visible in residential neighborhoods because of exhausted resources, cuts in funding and increased development along the Platte River Valley, says Parvensky.

The homeless have been pushed or crowded out of downtown and, often in the interest of their own safety, move into more residential neighborhoods such as Sloan’s Lake. But they are not particularly wanted by residents such as those in the Sloan’s Lake Citizen’s Group.

“Being homeless is not a crime,” says Garcia, “but sometimes it can feel like it is.”

END

This is the first in a series of articles profiling the homeless in North Denver. Next week, Yesterday’s Heroes, Today’s Homeless: the Plight of Homeless Veterans.

Captions:

A: Homeless teen, Sarah points with her trademark golf club to the place where the body of a 50 year-old homeless man, George P. Rael was found last Friday

B,C: Homeless teen, Sarah takes a nap in Sloan’s Lake Park where she has lived since she came of age and was let out of foster care.

D: Exercisers and the homeless frequently cross paths in Sloan’s Lake Park

E: K.C. and her two-year old daughter wait in Sloan’s Lake Park at dusk for her husband to return

K.C. waits in Sloan’s Lake Park with her baby for her partner to return.

Yesterday’s Heroes, Today’s Homeless: A Subsistence Living for Vets

by Ande Wanderer

For those who live indoors, rain or snow is a minor inconvenience on a day-to-day basis, but for the homeless, weather largely determines whether you’ll have a good day or a bad one.

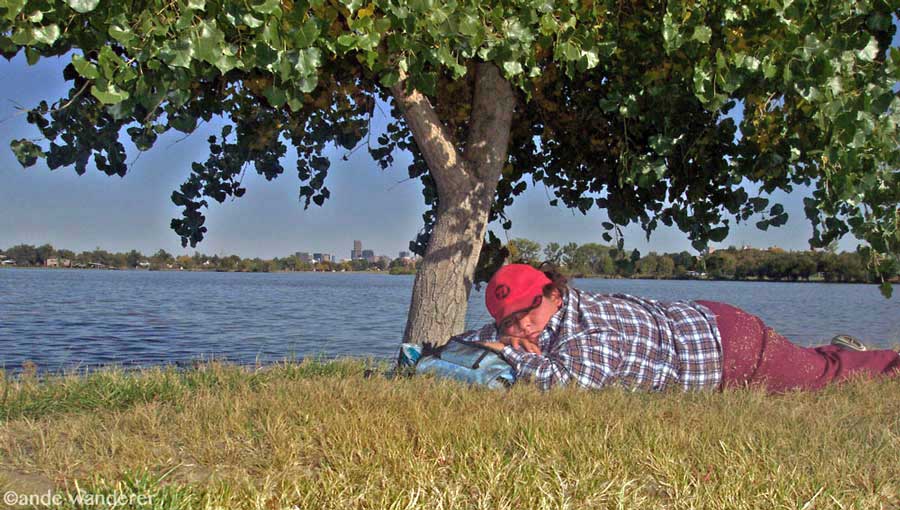

September 17th looked like it would be a good day for Dave Garcia. When he woke up early in the morning at Sloan’s Lake Park, it was warm and sunny, like a late summer day. A friend had given him a paperback thriller to read, and since it was only mid-month, his military pension check of $290 had not yet run out.

But by 9:00 p.m. fog, wind and drizzle had rolled over Sloan’s Lake and temperatures had dropped nearly 50 degrees during the course of the day. Garcia put on his warmest clothes and took cover under the awning in the back of Sloan’s Lake gym to try and sleep, but it was a rough night.

In fact, it has been a rough year. Garcia lost his job last February. Although he learned to be a generator mechanic in the army, and was once employed at Lakeside Amusement Park operating generators, he couldn’t find another job. A widower with no children, Garcia is among the 40 percent of the homeless men in Denver who are veterans, the majority of whom are in their 50’s and 60’s and served in the Vietnam era. Garcia had never before been homeless. For a while, he was able to stay at his sister’s house, but the landlord complained that she was breaking the terms of her lease by having others stay there. Garcia left, but his sister and her family still visit him in the park, sometimes with a picnic lunch.

Now that he’s on the streets, without a place to shower and a phone number to put on job applications, it’s virtually impossible to get a job, he says. Occasionally he goes to day labor companies, but the competition is tough. “There’s not much for a fifty-five year old,” he says, especially one with advanced arthritis and psoriasis. Instead, he spends his days sitting in the park, reading novels and newspapers, talking to friends and saying hello to friendly park regulars.

Garcia is not much of a drinker, but he has empathy for the folks in Sloan’s Lake who do drink.

“The only way they can get through it is by drinking,” he says. Garcia also refuses to panhandle, but with his typical gentle demeanor he says ‘random acts of kindness’ sometimes come his way. There was the day a woman walked up and said, “Would you accept this?” It was five dollars.

Another time a teenage girl on roller-skates gave her little sister three dollars to give to him. “You could tell it was her allowance or babysitting money,” says Garcia. Another guy regularly brings him McDonalds from across the street, he says. A few times a week Dave straps on his backpack and heads to the Denver Dream Center, a church outreach facility at Colfax and Harlan Streets.

“If you go to the service they give you something to eat,” he shrugs. “But I’m a Catholic.”

Another Sloan’s Lake Park resident is Tim, also a Vietnam Veteran, who saw heavy combat during his 12 years of service. He admits that when he first returned from the war he ‘had some problems.’ The ‘shell-shocked’ syndrome of post-combat veterans would come to be named and added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1980: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Although Tim hasn’t officially been diagnosed with PTSD, it is prevalent in Vietnam Vets. According to the Colorado Coalition of the Homeless, an estimated three-quarters of vets who saw combat have lingering mental and substance abuse issues.

Tim says after he returned from the war, tormented and shell shocked and unable to re-assimilate into family life, his wife took the children and left. He hasn’t seen them since. He realized alcohol was part of the problem, so he gave it up. He says he hasn’t had a drink in 30 years. Local business owners and other who live in the park say it’s true — they’ve never seen him take a drink.

Apparently, quitting alcohol wasn’t enough to prevent Tim from his present fate. He lost his job in Phoenix one year ago when the place he worked for went out of business. He couldn’t stand the summer heat in Phoenix, so he headed back to his native Denver and landed in Sloan’s Lake. Tim receives a military pension and food stamps but the benefits are not near enough to afford an apartment in Denver. At 61 years old his health problems include severe back problems, emphysema and an inflamed blood vessel in his leg.

According to the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, 275,000 vets are homeless on any given night nationwide and over a half a million vets will experience homelessness over the course of a year. The VA serves about 40,000 vets annually, meaning they reach less than ten percent of their target population.

In Denver, many other private and governmental services that cater to the homeless are downtown. Recalling the string of seven brutal murders and other beatings of homeless people in 1999, Tim says he avoids downtown as much as possible.

“I wouldn’t go to one of those shelters if they paid me,” he says. He mentions one shelter that gives beds on a first-come first-serve basis — if he gets near the front of the line, a younger guy might pick a fight so they can take his place, he says.

He also worries about his warm clothes and bedroll getting stolen. Tim has applied for veteran disability benefits and subsidized housing, but as the nights get chillier in the park, the process is taking longer than he would like.

In the meantime he fights a different kind of battle than he did as a ground trouper in Vietnam. Two weeks ago, ‘Little Mike’ Quintana, manager of the Sloan’s Lake boxing club heard some commotion in the rear of his building. He opened the back door of his club and scared off some young men on bicycles that he suspected were going to rob or beat Tim while he slept. Then, Tim discovered the corpse of another homeless man, George Rael in the lake last week.

Now that the first of the month has rolled around, both Tim and Dave have received their pension checks. They are both temporarily staying at cheap motels. It’s a ‘mini–vacation’ from the streets, but they’ll be back on the battle lines next week.

END

Captions:

#6: Dave Garcia, 55 spends much of his time reading in the park.

A,B: Now that Dave Garcia has checked into a hotel for a week, a couple, including another homeless vet, have taken over his camp.

Sarah points with her golf club to where the body of homeless man George Rael was discovered

Addendum

The issue of homelessness in Denver and indeed metropolises throughout the U.S. has skyrocketed since this article was published.

Since that time, I witnessed the increased cost of housing price out a friend, who when we met 20 years ago had a good job in a tech company and lived in a rented one bedroom apartment. A couple of years ago he was featured as one of the residents of Denver’s Beloved Tiny Home Village. The small project — there are eleven tiny homes — is the first tiny home development aimed to address Denver’s homelessness problem.

Housing under twenty people is a drop in the bucket though.

Today, there more than 30,ooo homeless people in Denver according to a report by the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative.

The increase in housing costs in Denver since then has only made the problem worse for people on tight incomes such as Katie Tate, reports channel 7.

In Sloan’s Lake a plan for a development that would be 60% median income housing with a few units reserved for former homeless families was approved by city council in 2019.

Five percent of the units are reserved for those at 40% of the American median income.

In a $55, 596 study by the University of Denver’s Graduate School of Social Work, 61% of respondents in the Denver metro area surveyed cited the cause of their homelessness as ‘unable to pay rent.’ What a revelation!

Reporters have no problem finding facts and figures on homelessness. There are lots of studies conducted and many organizations working on the problem, so it’s frustrating that the issue has only gotten worse.

It does look like the Covid pandemic forced Denver to come up with some reasonable solutions quick. NBC reports (video) that the city set up two sanctioned camping sites with ice fishing tents and sanitation facilities. It costs the city $25 a day per person. To put that in perspective, it costs over $115 per day for each person incarcerated in a Colorado jail or prison.

____________________________________________________________________

As a side note, Mike Quintana, quoted in the article, is the kind of guy reporters love. He has his fingers on the pulse of what’s going on in his little sphere of the neighborhood and he is a straight shooter. Funny to see that the story of his arrest for doling out some old school justice to graffiti taggers at his gym in 1998 somehow made it into school materials for children.