Marijuana didn’t become legal in Colorado overnight. Nearly fifteen years before recreational weed was legalized in the Centennial State, advocates and activists battled anti drug crusaders in the effort to pass Amendment 20, legalizing the use of medical marijuana.

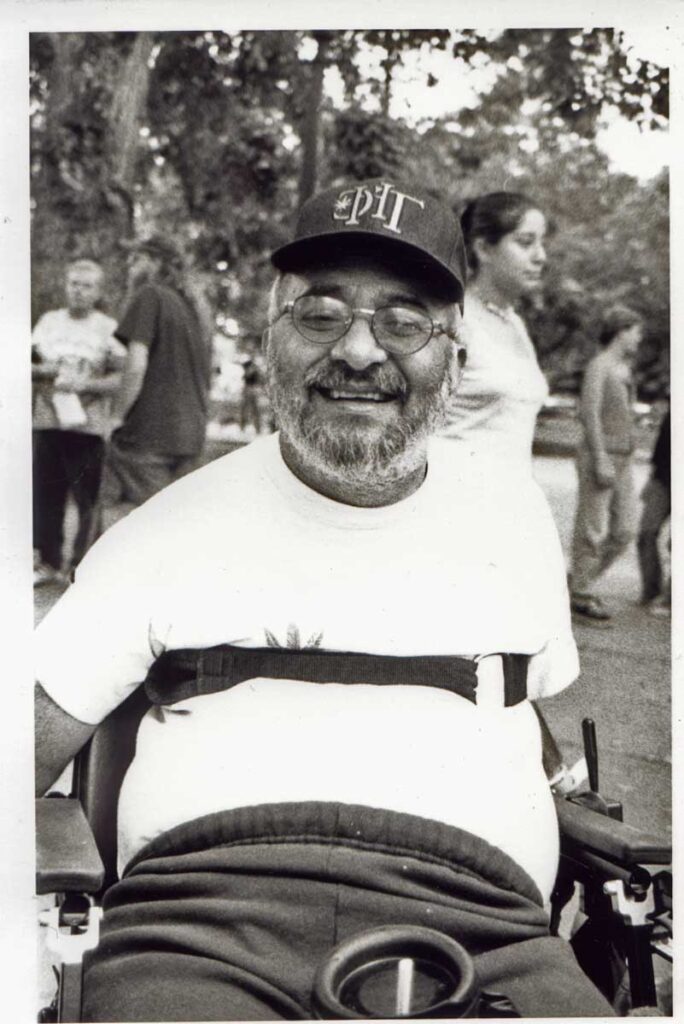

Norman Abeyta isn’t your average pothead. After all, as someone who struggles to perform simple tasks such as brushing his teeth and getting a drink of water, he also manages to run his own business, participate in letter writing campaigns and organize protests —hardly the lethargy you’d expect from a regular stoner.

Especially a stoner who is a quadriplegic.

It was the summer of 1972, right after he completed his senior year in high school, when Abeyta’s life changed forever. He was driving with a friend on highway I-25. In those days no one wore their lap-style seat belts. There were no air bags. When the car he was in hit a truck, Abeyta was thrown through the windshield.

In an instant, the plans he had carefully laid out for his life dissolved.

Instead of going to study forestry at Colorado State University on a full scholarship in the fall, as he had planned, he would spend the next six months in the hospital learning how to adapt to his new life.

Trading Pills for Pot

Abeyta says that for him using marijuana isn’t mere pleasure seeking — it’s a medical necessity. Smoking pot, he says, reduces involuntary muscle spasms that are sometimes so severe they catapult him from his wheelchair. It also helps with a condition common to people with spinal cord injuries called autonomic dysreflexia, which causes blood pressure spikes unexpectedly, sometimes causing strokes.

While the mind-altering narcotics prescribed for this condition can take thirty minutes to take effect and are addicting, marijuana works almost instantaneously. Abeyta says he functions better on pot than on pills.

“As it is, it costs me $.50 for every prescription with Medicare, if I wanted (the pills), I could have them. Vicodin is an opiate and a very strong narcotic. It’s medically unnecessary. Unless I need it, I figure, why take it?” says Abeyta.

“During the day, while I’m up in my chair, I don’t really want to be all doped up.”

Amendment 20: Medical Marijuana

If Amendment 20, legalizing medical marijuana, passes on November 7, Abeyta and someone he designates as his primary caregiver will be able to grow marijuana and possess up to two ounces of it at a time.

To participate in the program a patient will need a recommendation from their doctor, who will be required to discuss the ‘risks and benefits’ of marijuana use with the patient.

They will then pay a fee (to offset startup costs of the program) to receive a registry identification card from the state health department.

Patients are then legally able to possess up to two ounces marijuana, and grow six cannabis plants, of which only three can be mature at a time.

They are prohibited from using pot in public, while driving, or in other situations that might endanger the public. Patients who have a chronic condition, or remain ill, will be required to re-register annually.

There is little reason to believe the amendment will be defeated. In every state where similar legislation has appeared on the ballot so far —California, Arizona, Florida, Oregon, Washington, Maine and Alaska, it has passed.

It probably won’t hurt that Colorado also ranks fourth in the nation for marijuana use by its residents. And in a recent survey by the Rocky Mountain News, 71 percent of voters polled were in favor of the bill.

Citizens Against Legalizing Marijuana

It’s these numbers that have people like Eleanor Scott of Citizens against Legalizing Marijuana (C.A.L.M.) worried. A foot soldier in the drug war since Nancy Reagan’s, ‘Just Say No’ campaign, Scott says the amendment would send children the wrong message — if marijuana is officially sanctioned as medicine, they will get the idea that it is okay for them to try it too.

C.A.L.M. has some heavy-hitting political figures and organizations in their corner — State Treasurer, Mike Coffman, Colorado Attorney General, Ken Salazar, and Governor Bill Owens, who has referred to Amendment 20 as the ‘Drug Dealers’ Full Employment Act.’

Predictably, law enforcement groups such as the Colorado Association of Chiefs of Police are also opposed, as well as the American Medical Association and the Colorado Academy of Family Physicians.

“The big picture is that we’re voting in an amendment by popular vote, it’s not going through an approved scientific process,” says Scott. Amendment 20 is nothing but a veiled attempt to legalize marijuana entirely, she says.

“If someone in her family had cancer or AIDS and had wasting syndrome, and used it — if it was a personal experience and not a political experience — than she would perceive it differently,” says Martin Chilcutt, a retired psychologist and the man responsible for bringing the medical marijuana movement to Colorado.

After California passed Proposition 215, ‘The Compassionate Care Act’ approving medical marijuana in 1996, Chilcutt decided to work for a similar initiative here.

His motivation was the AIDS and cancer patients he treated who were using pot with their physicians’ consent and appeared to be helped by it, but these patients feared getting in trouble with the law.

Chilcutt, himself a cancer survivor, has first-hand experience of using marijuana as medicine. Although he says he never used marijuana recreationally, knowing it helped his patients, he tried it when he was undergoing cancer treatment eight years ago. He found it helpful in managing pain, anxiety and sleeplessness.

Chilcutt joined forces with Americans for Medical Rights (AMR), the deep-pocketed California-based group that has funded medical marijuana campaigns in other states. In order to improve upon California’s act, which many say was riddled with loopholes, the group, that became known as Coloradans for Medical Rights, hired attorneys to draft Colorado’s amendment.

“They took California’s initiative,” says Julie Roche, Campaign Director for Coloradans for Medical Rights 2000 (CMR) “and decided, they wanted to make it a much more restrictive initiative and make it clear to Coloradans that this is just a medical issue.”

Voters may recall that the Medical Marijuana Amendment appeared on the 1998 ballot. Results were never tallied however, because then Secretary of State, Victoria Buckley, effectively scuttled the vote by claiming — a week before the election — that there were not enough valid signatures for it to appear on the ballot in the first place. There was no way CMR could challenge the assertion before the election, but they were eventually able to prove that they did indeed have enough signatures.

After Buckley’s untimely demise last year, a box of additional petitions in support of the amendment were found in her office.

“She was part of the concerted conservative right wing effort in the Republican Party to keep this off the ballot,” says Chilcutt, who previously took Buckley to court when she refused to recognize the amendment.

“The State Legislature did not want this on the ballot.” Nevertheless, it was automatically put on this year’s ballot, without CMR having to again take the matter to court.

Big Pharma Solution: Pot in a Pill

A 1999 Institute of Medicine report, conducted at the request of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy was organized to settle some of the questions surrounding medical marijuana.

The study’s conclusions provide evidence to support the arguments for both those who deem marijuana medicine and those who don’t. The report sites the drawback of delivering active ingredients through smoking marijuana but states, ‘there are patients for whom smoked marijuana might provide relief,’ especially cancer and AIDS patients who use it to control nausea and pain.

For Multiple Sclerosis and other diseases that cause spasticity, the results were ‘moderately promising.’ The authors warn that because of side effects such as lung damage and weakening of the immune system, marijuana should be used only as a last resort.

The report also noted that the future of marijuana as medicine lies in other rapid-onset delivery methods, such as inhalers, that remove the inherent dangers of smoking. For patients who are sick and currently smoking marijuana they admit, “the adverse effects of marijuana use are within the range tolerated for other medications.”

No one disputes the fact that marijuana’s active ingredient, tetrahydrocannabinol or THC can help patients. As opponents of Amendment 20 often point out, there is a FDA-approved THC drug in pill form called Marinol already on the market.

But AIDS and cancer patients who undergo chemotherapy, or take dozens of pills a day say smoking marijuana is what helps them to decrease nausea so that they can keep food and medications down. Patients with other ailments say Marinol takes too long to work its way through the blood stream and just isn’t as effective.

“I take so many damn pills everyday,” says Ror Poliac, a 44 year-old with Multiple Sclerosis who has tried Marinol.

“It’s just another pill, sure it has THC but who knows what else it has? I’m tired of taking pills that might have a dangerous reaction with something else I’m taking.”

Perhaps no one in Colorado would be more pleased to see Amendment 20 pass than Ror Poliac.

Since he was diagnosed with MS 12 years ago, his body has slowly deteriorated, affecting his sight and ability to walk, talk and control bodily functions. He found pot helpful to gain weight when he first got a colostomy bag. He says now he only uses it at night to counteract speedy prescription medications that keep him awake. Without pot, he says he can’t get to sleep at night.

Even though he is a very moderate pot user, only taking a couple of puffs at nighttime, Poliac’s decision to use marijuana medicinally and speak out about it has created plenty of problems in his life.

He is currently being prosecuted in Arapahoe county (where Pat Sullivan, a former C.A.L.M. member is sheriff) for growing four pot plants in his home, in an effort to save money. His lawyer, Warren Epson hopes that if the amendment passes, the case will be dropped.

“I would be shocked if Arapahoe County continued to prosecute a wheelchair bound gentleman whose doctor is sitting there saying, ‘marijuana is the only thing that works for him.’” Especially when there is “absolutely no proof that he was doing anything besides growing it for himself,” he says.

Poliac’s father is former Republican Legislator, Ted Poliac. Poliac says his parents are so upset about him being a public figure in support of medical marijuana, they haven’t talked to him since May.

“Sometimes I don’t even understand what planet my dad is from,” says Poliac.

“It’s just my choice of medication that is the thorn in his side.”

A Flawed Amendment?

Despite the public approval of Amendment 20, many who have scrutinized the law are able to point out what they perceive as its flaws.

People on both sides of the fence argue that medical marijuana should not be a constitutional amendment. Anti-drug activists say the Constitution should be a place for only fundamental laws such as the structure of state government. Pro-medical marijuana activists say it is difficult to make changes to amendments and later correct any flaws in the legislation.

Many are suspicious of the motives of Americans for Medical Rights, the group funding CMR.

It’s led by New York philanthropist George Soros, Progressive Auto Insurance CEO, Peter B. Lewis, and John Sperling, President of the Apollo Group, a holding company for adult education programs.

“There’s something else on their agenda beyond the compassion of good medical care,” says Dr. Frank Sargeant, a C.A.L.M. supporter whose sentiment is echoed by those for and against medical marijuana.

Even Chilcutt himself, who was eager to join forces with AMR early on, says they are ‘big business.’ He parted ways with them after the last election.

“The law isn’t specific enough,” says Norman Abetya. Although he would benefit from the decriminalization of medical weed, he is still undecided on how he will vote on 20. If he were free to grow his own pot, he says his costs would go from $250 a month, down to $25. More importantly, his parents, whom he lives with, would be off the hook legally.

“Every reporter I talk to I say; ‘Yes, we want it passed. Yes it’s good for Colorado,’ but I still have a few reservations,” he says.

For one, spinal cord injury isn’t specifically cited in the amendment, but he would probably qualify under ‘other debilitating circumstances’— the very part of the amendment opponents say opens the door for just about anyone to get a doctor’s recommendation for medical marijuana.

Despite any misgivings, “In the end, I probably will vote for it,” he says. “It’s better than nothing.”

CMR’s Julie Roche says they’ve done the best they can to take the middle road, to ensure that the amendment is passed.

“We get criticisms from both sides,” she concedes. “On the one side is the general legalization movement and they think it’s way too restrictive, including the registry. And then on the other hand you have anti-drug people and they think there’s all these loopholes in it. ”

The restrictions on the quantity of pot patients will be legally allowed to possess is where CMR made its biggest compromise, says Roche.

“The opponents say, ‘That’s way too much for a person to have — that’s too much for personal consumption.’ And the other side says, ‘That isn’t enough.’ I think we are somewhere in the middle with the limits,” she says. “If there weren’t limits we’d have even more opposition.”

The registration system for patients was something unique to Colorado’s proposed legislation. It was drafted so that police would not be forced to take the word of anyone caught with marijuana who claimed that they were using it for medical purposes — they would have access to a database to verify these claims. For patients, the registry system is seen as a way for them to defend themselves if caught with a stash of pot.

But the registry has been another aspect of the amendment both opponents and supporters of medical marijuana dislike. Robert Lewis, a Stake President of the Mormon Church and a member of C.A.L.M. says since they can possess two ounces at a time, once a patient is registered and gets a card, “He can be completely stoned for up to a year.”

Some say the registry, though it will be confidential, could compromise privacy because it authorizes state access to medical records, an especially sensitive issue for AIDS patients. Others, including Abetya, fear it could put patients at risk to be prosecuted under federal law. Roche counters, “In other states the registry hasn’t been used to go out and persecute people who are on it.”

Perhaps the biggest fault many find with the amendment, is that it doesn’t provide for any legal means of distributing the marijuana — patients who don’t grow it, will still have to buy it from illegal sources.

Roche says the reason they did not deal with distribution on the initiative was that it would violate what’s called the single-subject rule for new legislation. And as long as marijuana continues to be a Schedule I drug, the most serious in legal terms, addressing distribution is virtually impossible.

Chilcutt says if the amendment passes, he plans to establish a therapeutic cannabis cooperative operated for and by patients to remove any difficulties or dangers associated with purchasing marijuana on the street. But that could prove to be tricky.

Whatever the state laws may be, growing, possessing and distributing marijuana will still be illegal according to federal laws.

The U.S. Department of Justice has been desperately trying to get state medical marijuana initiatives overturned, and on August 30 the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Oakland’s Cannabis Buyers’ Cooperative to shut down.

Until a recent injunction, doctors in California were informed by federal authorities that they could lose their licenses to practice medicine if they recommended marijuana to patients. Their marijuana prescriptions would be ‘aiding and abetting’ a federal crime.

The most dramatic case in the federal crackdown was the 1997 raid on the ‘Cannabis Castle,’ a large cannabis cooperative established in Bel Air soon after Proposition 215 passed in California.

The founders of the Cannabis Castle didn’t make an effort to hide their activities and about 4,000 pot plants were seized in the raid.

Thirty year-old Renee Boje, who worked at the cooperative, was charged with growing and trafficking marijuana because during surveillance she had been seen watering plants that were on a balcony.

Boje fled to Canada and applied for refugee status on the grounds that she faces a grossly disproportionate sentence —a minimum of ten years in prison — and inhumane conditions such as overcrowding and possible rape and torture in jail, as documented by human rights groups such as Amnesty International.

The U.S. government is demanding Canada extradite Boje. The case is now in the hands of Canada’s Federal Justice Minister, Anne McLellan, who is expected to make a decision soon.

Peter McWilliams, an AIDS and cancer patient, medical marijuana user and advocate was also charged after the raid. McWilliams agreed to plead guilty to his charges and was released on bail. He was subjected to drug testing after his release and was therefore unable to use marijuana, which he credited with saving his life. He died in June after choking on his own vomit while awaiting sentencing.

If Amendment 20 passes there will probably not be any ‘Cannabis Castles’ sprouting up in Colorado because of the built-in legislative restrictions. But some worry patients will still be vulnerable.

“The one thing I don’t want to see come out of it,” says Laura Kriho of the Colorado Hemp Initiative Project, “is that now patients are going to get a false sense of security, that ‘now we’re safe’ because really their protections are very few.”

Ror Poliac seems to have a more idealistic view of the situation; “I just can’t see anybody, including the legal profession, worried about it. It’s just such a small amount and it gives me some satisfaction. It’s America — it’s a compassionate country I thought.“

END

Appendum

This cover story for the Rocky Mountain Bullhorn was one of a number of stories I wrote on what was — at first — a movement to legalize medicinal marijuana in Colorado. Colorado was still a red state back then and there was a strong, organized opposition to medicinal weed.

Anti-weed crusader, Scott was right about the medicinal use of pot leading to full legalization, although that was considered virtually impossible when I wrote this article.

Colorado’s Amendment 20 passed in 2000 with 54% of the vote.

It turns out that the anti-marijuana group C.A.L.M. is still going. They now produce literature that correlates legal weed with increased crime and highlighting that marijuana is still a schedule I drug federally.

Remembering Colorado’s Legal Pot Pioneers

It pleases me to have stumbled across this old article, because a few of the people I interviewed were pioneers in the medicinal marijuana movement, including Norman Abetya (the quadriplegic pot user) and Ror Poliac (the M.S. patient who got thrown in jail for attempting — unsuccessfully — to grow his own pot).

Both men were seriously disabled and sought out pot to alleviate symptoms in lieu of much stronger, addictive medications.

Laura Kriho (who I did a couple of other stories on when she made national news for her Contempt of Court conviction for exercising her right to Jury Nullification) and Martin Chilcutt, the author Colorado’s Amendment 20.

I recently came across a nice feature on Martin Chilcutt, that looked back on his time spearheading the legalization movement in Colorado through his advocacy group, Coloradans for Medical Rights.

Unfortunately Norman Abetya passed away at the young age of 51 in 2007.

Ror Poliac ‘the poster boy of legal weed’ passed away in 2007.

Kriho passed away in 2017.

Mile High potheads have these folks to thank for paving the way for legal weed in Colorado via their advocacy of medical marijuana and patients’ rights.