Buenos Aires, Argentina

Sultry tango, a few succulent steaks, a bit of liposuction perhaps.

Now that Argentina has stabilized considerably after its 2001 economic collapse, tourism in the capital that offers ‘European elegance at Latin American prices’ has exploded.

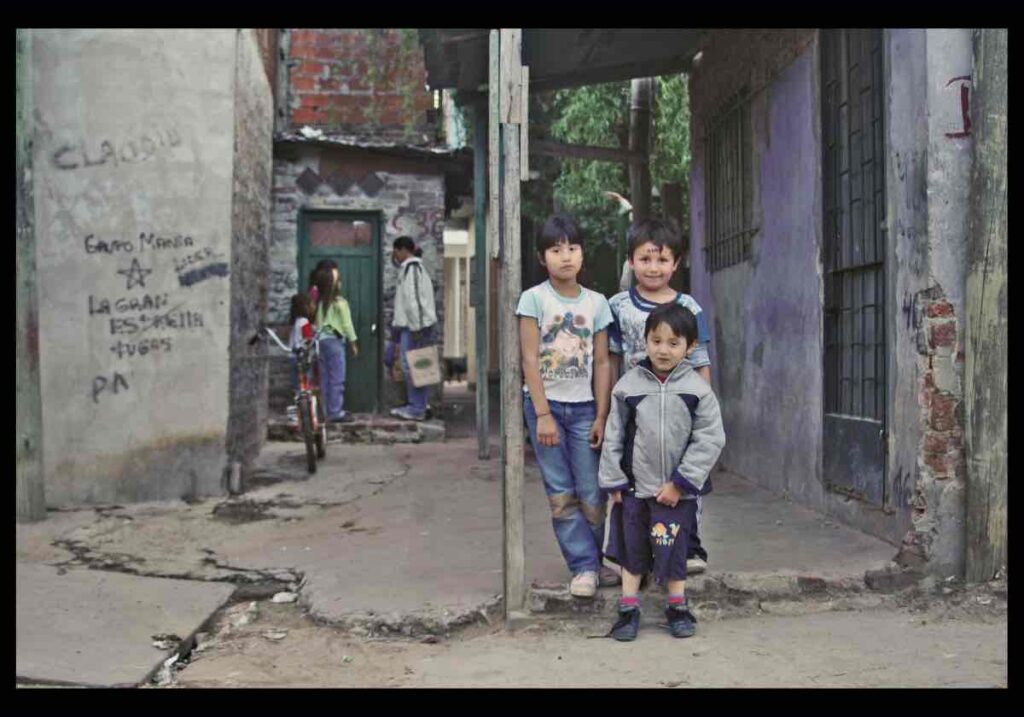

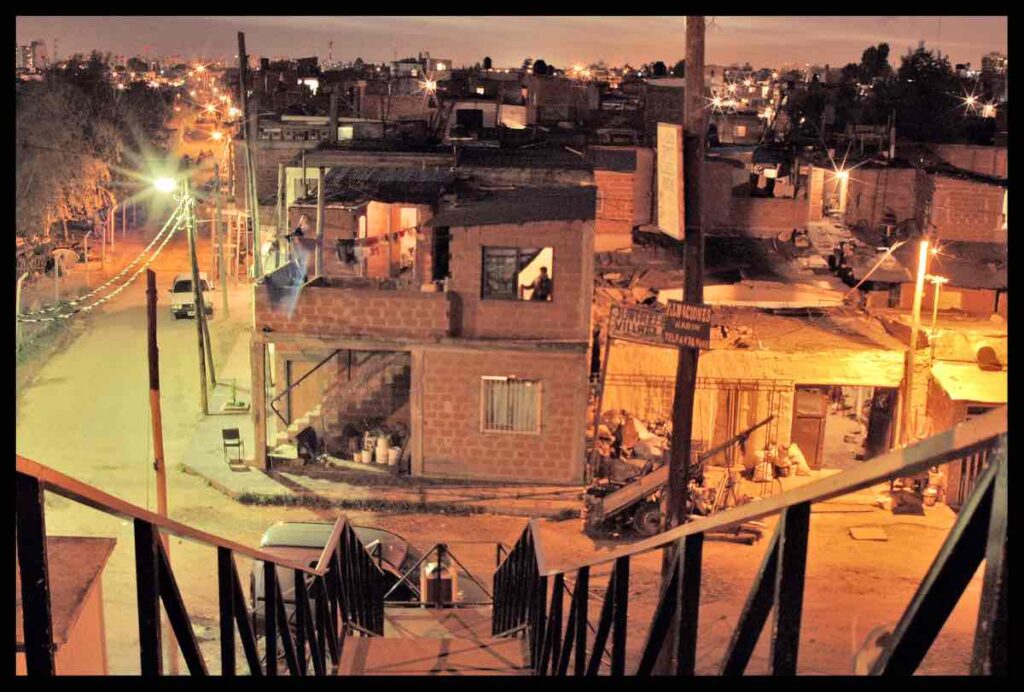

It can be easy to forget while wandering around upscale neighborhoods with names such as Palermo Hollywood that in some corners of this city, people live in houses constructed of scrap, the air smells of burning garbage and children have little more to play with than soccer balls made out of plastic bags.

Although the average visitor — and even most Argentines — never visit the ‘villas miserias,’ or ‘miserable villages’, one tour here offers a look at life inside the slum.

Other cities such as Río de Janeiro and Johannesburg already have thriving and controversial ‘slum tour’ businesses.

In Buenos Aires, the company Tour Experience has been hosting ‘villa tours’ since 2005, but only a few dozen people have taken the tour thus far.

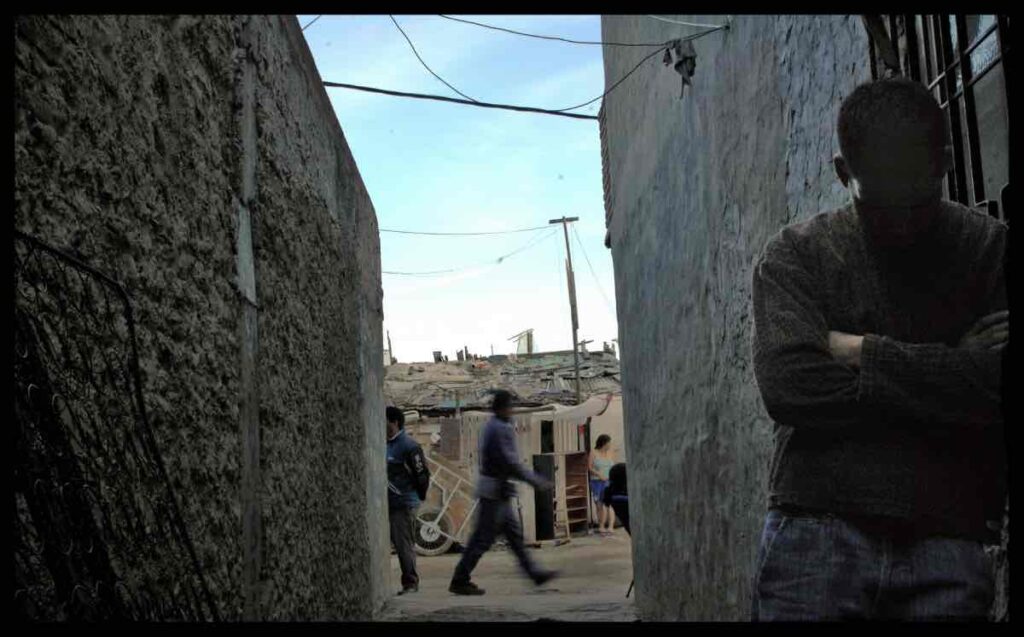

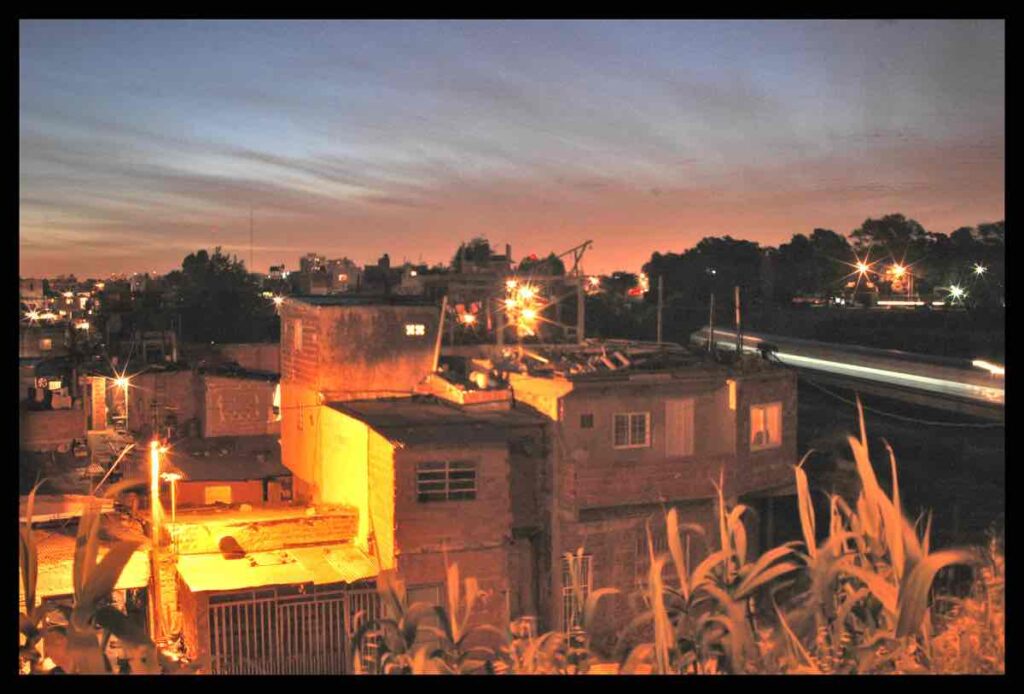

The tour takes visitors to the city’s largest slum, Villa 20 where nearly 30,000 people live in crowded shacks packed onto 28 city blocks.

––––

Living on $50 a Month

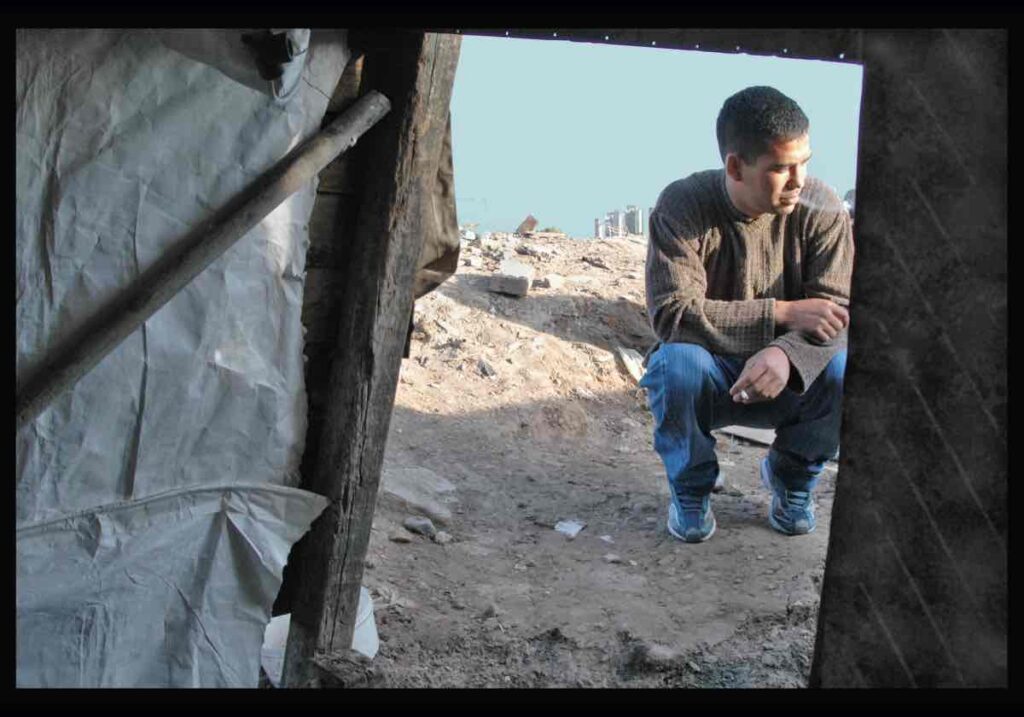

Francisco Balbuena lives on $50 a month, ten dollars less than the price of the Villa Tour that goes through his neighborhood. The one-room shanty where he lives has a dirt floor. A seat-less toilet sits in the middle of the room, even though there are no municipal sanitation lines here.

When it rains the house becomes inundated with sewage. The lingering smell never really goes away.

On a weekday afternoon Balbuena, sits outside his house smoking and drinking soda pop. A few meters away sits a ‘car graveyard’ that leaks poisonous fluid and is the breeding ground for rats.

Beyond that, a white tower, rises up from the city’s now-defunct theme park across the road, a sort of totem for the people that live here.

––––

Reality Tour?

“You haven’t been to Buenos Aires until you’ve been to a villa,” says Martín Roisi, a film and TV producer and founder of the company, Tour Experience.

Roisi became acquainted with Villa 20 four years ago when he organized a casting there.

He already was a fan of cumbia, the simple music with clever, explicit lyrics that pump throughout the neighborhood. He says he witnessed an authenticity in the residents, 60% of whom are Bolivian and Paraguayan, that inspired him. Looking to spend more time there, he started his tours.

The tours have received considerable criticism locally, but Roisi insists his aims are altruistic.

“The idea isn’t to put poverty on display,” he says.

“The idea is to share the culture of the neighborhood.”

He says all of the income from the tours goes toward a soup kitchen in addition to various creative projects in the villa.

Kathleen Lingo is a New York City-based filmmaker took the tour last year and returned to make a documentary about life the villa.

“It’s not what you expect. When we were on the tour we were inspired by what a great place it was,” she says.

“From the outside, it seems sad and disenfranchised, but the social aspect of the villa is great. Not to paint it with a rosy lens. It’s life — in all its horror and beauty just like anywhere else.”

Lingo’s documentary focuses on the lives of three young women from the villa and is being made in conjunction with Project Odisea 20, what Roisi refers to as a ‘ministry of culture.’

Villa residents were trained and employed to work on the film. Odisea 20 also has a small record label producing cumbia music, a publishing house, a mini-movie theatre and an art gallery run by residents.

All of the do-it-yourself projects are featured stops on the villa tour.

––––

‘The Villa is Paradise’

Chaco, a poet Roisi helped to get cast in a film, says, ‘The villa is paradise.’ Maybe only through the eyes of a poet, but some of the foreign visitors who come here are compelled to return.

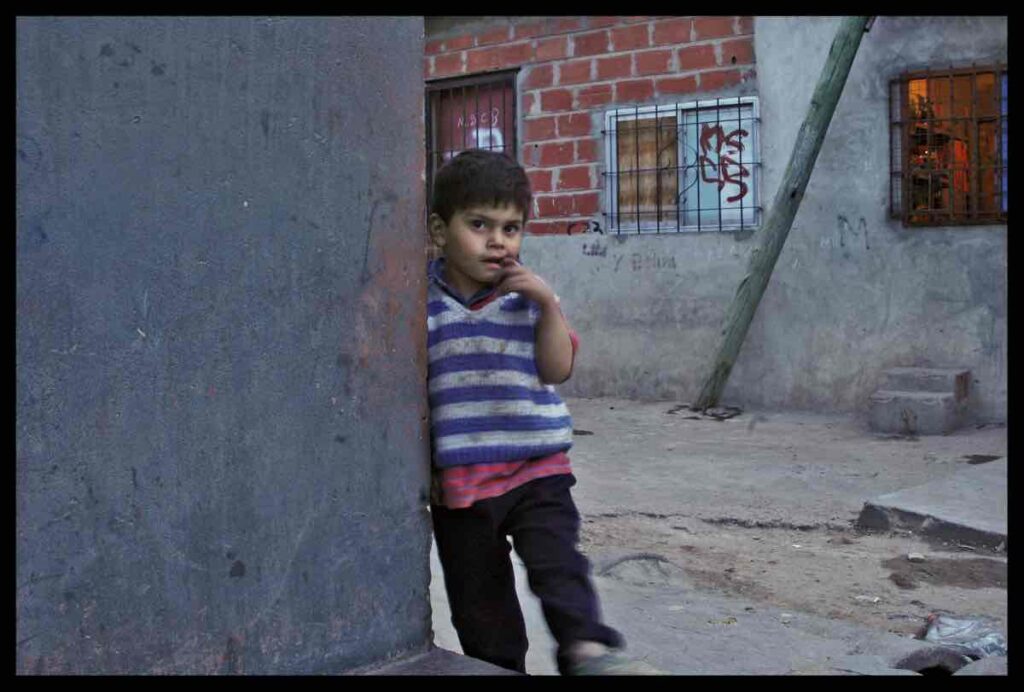

Heike Thelen, a German native and six-year resident of Argentina, visits the villa every week with her three-year-old son to lead the children’s art workshop in one of the villa’s soup kitchens.

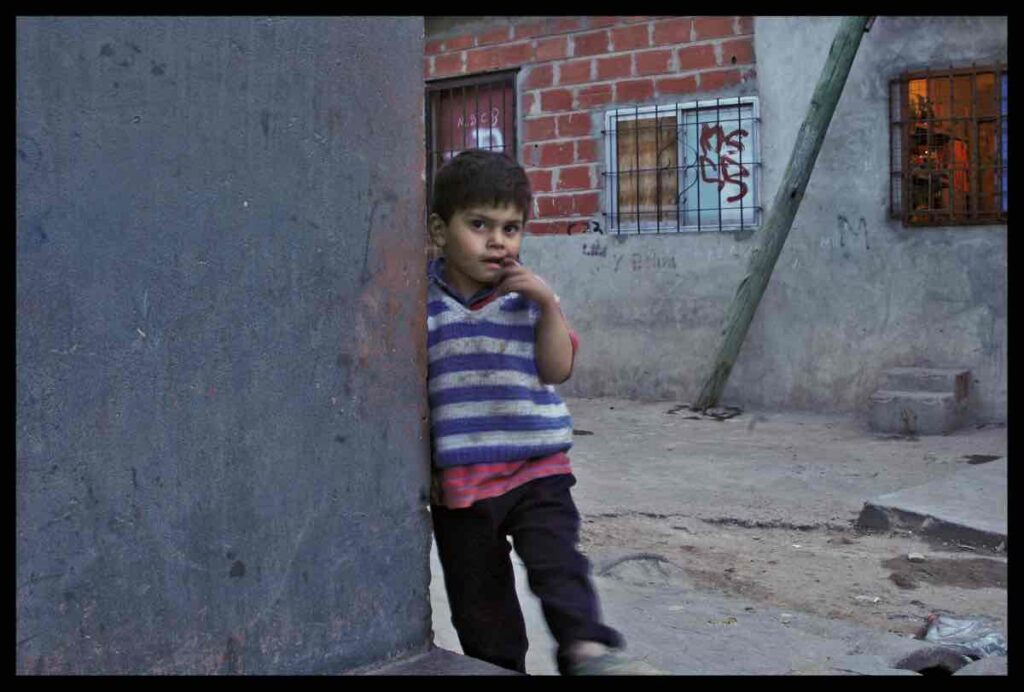

“My kid is a villa kid,” she says. “I want him to experience life here. Look around,” she says waving toward a group of children playing.

“The ground is full of broken glass, it’s totally contaminated and the kids have no toys, but they’re happy.”

As the beer flows and the sausage cooks at Las Breñas, the villa’s sport and social club, where a ‘working man’s barbecue’ is served at the end of every tour, mutual curiosity prompts residents and visitors to interact.

One of the regulars here is Silviana Peredo Días, a 32-year-old mother who earns $50 a month caring for disabled residents in their homes.

She lives with her common-law husband, four kids and niece in a two-bedroom apartment, in one of the ‘monoblock’ units built at the periphery of the villa. The massive housing complexes are part of the city’s urbanization plan for the area. The family has a subsidized 30-year mortgage on the apartment.

Días became a sort of local celebrity here after Odisea’s 20’s Interama Books published her book entitled ‘Twins.’

It is a compilation of the adolescent journals of her deceased twin sister and herself. In her spare time, Días volunteers as the director of the villa’s creative writing program for teens.

“We’re not millionaires or anything but we’re doing okay,” she says. “This is home.”

Her husband, Julio Cesar Alvarez, who works as a bodyguard on the tours, agrees.

“We’re happy,” he says. “We want to continue living here, but we want the neighborhood to improve.”

—-

Ande Wanderer is a photographer and writer based in Buenos Aires.

Appendum

I titled this, ‘Tango, Steaks, Slum Tour? Discovering the Grittier Side of Buenos Aires’ but I am always more than happy to defer to a good editor.

My original also said, ‘Other major cities such as Río de Janeiro and Johannesburg already have thriving and controversial ‘slum tour’ businesses.’

I had a bodyguard for this story, thus it was one of the few times I have taken a professional camera out on the rougher streets of Buenos Aires.

I’m more than happy to uncover stories in rough and tumble places but sometimes foreign editors in NYC don’t quite grasp that the risk of carrying a fancy camera in the dangerous barrios of Buenos Aires deserves extra hazard pay.

Unfortunately, Joe Wolek, an American photographer stabbed (link in Spanish) in the next neighborhood over in La Boca found out the hard way.

His family set up a GoFundMe to brace for incoming bills, but an incredible heart surgeon saved his life, and thanks to Argentina’s universal healthcare it didn’t cost him a dime.